Homecoming—Clark Gable

The statue, “Miss Liberty” all those boys in uniform crowded around the rail called it, was out there somewhere in the mist, so close that Ulysses felt he could touch it. Above the blasts of the transport’s foghorn, above the shrill whistles of the tugs, he could hear other sounds, the sounds of home, the whisper that was really the shouting of the welcoming crowd on the pier, rising and falling above muted strains of a brass band. Punctuating all of them was the piping staccato of automobile horns, the trucks, taxis, and the endless stream of cars so characteristically New York. Yes, they were ail there, right behind the fog, but the Europe he had just left seemed much nearer to Dr. Ulysses Johnson, Major in the US. Army Medical Corps. In less than an hour he would be in New York and in scarcely more than a day later he would be home—home with Penny. But there was none of the elation that should have come, thinking of Penny. When he had left, the only thing he had to hold on to had been this homecoming, but now that it had come the taste of it was like ashes in his mouth. Even Penny, most of all Penny, seemed like part of a dream he had dreamed and forgotten long ago.

They had once been so happy with each other, and in their gracious life that had seemed to leave nothing to be desired. Success had come easily to him and he had escaped the gruelling grind so many of his colleagues were still going through. It amazed him sometimes how he had become the most fashionable surgeon in town, while men he had thought far more promising than himself had been—well, grubbing along was really the only way he could describe it.

Men like Bob Sunday, for instance, who was still practicing down in that dreary slum where he had first hung out his shingle. Chester Village it was called, though there was nothing about that crowded malaria infested tenement section to suggest the wide spaces and charming houses and gardens its name would imply. Ulysses had always felt Bob must have been lacking either in nerve or ambition to stay there year after year. But sometimes he made him feel guilty, too, like the time Ulysses had promised to go down and talk about the slum clearance project the other was so excited about putting into effect.

Ulysses had completely forgotten it was Penny’s birthday, so he had put Bob off and spent the afternoon with her at the club. That was only a few months before Pearl Harbor and the next time he had seen Bob was at the farewell cocktail party Penny had given the evening before he left for camp.

He had worn his uniform and for once he didn’t feel that twinge he’d felt before-after disappointing Bob. Instead, he felt superior to the other in every way now, not only in the material way he had always had, but in the more subtle one of conscience. After all, wasn’t he serving his country while Bob was still in civilians?

Maybe he had been a bit pompous, a bit smug, as he talked of what he was doing. For suddenly Bob had lashed out at him. “Look, Lee, don’t talk to me about issues,” he had said.

Ulysses hadn’t been put off. “Your country’s been attacked!” he reminded him a little too sharply.

Bob had taken a deep breath then and let him have it. “When you have the guts to tell me my country’s been attacked, implying that I’m not doing anything about it, that’s pretty hard to take. Over there in Chester Village men have been dying for years. Children are dying just for the lack of decent care. Malaria, malnutrition, hookworm! My country at| tacked? You’re darn right it has been. For a long time! But did you care? And don’t kid yourself about that uniform you’ve got on. You’re in it because it’s the thing to do right now, because everybody else is doing it. Get wise to yourself, Lee!”

That had washed them up completely. A friendship of years, gone, just like that! He had wanted to forget it, the way he always did unpleasant things. And yet he couldn’t. It was as clear to him now as the day it had happened. Much clearer to him than Penny was. He tried to think of her then, of the fun they’d always had, of the excitement of being with her. He tried to recapture that feeling he’d had the morning he kissed her goodbye, and the loneliness that had come afterwards when he thought of her. But even the loneliness couldn’t come through to him now, not with that other loneliness which seemed to be a part of his very bones, that’s how deep it lay inside of him.

“Snapshot,” he whispered and even her name seemed a part of him. “Snapshot.”

It was on the transport taking him overseas he met her. She was a striking-looking girl with that yellow hair of hers and those deep violet-blue eyes, but he hadn’t noticed her any more than he had the other nurses in his outfit, not with every thought he had back home with Penny, continually in his mind.

“I wonder where we’re headed for,” he had said to Dr. Silver, one of the older officers, as they lounged comfortably on deck that evening. “Can’t be Africa, because that campaign’s in the bag now that Montgomery’s got Rommel on the run. Probably won’t be long before the whole war’s over, now that we’ve come in.”

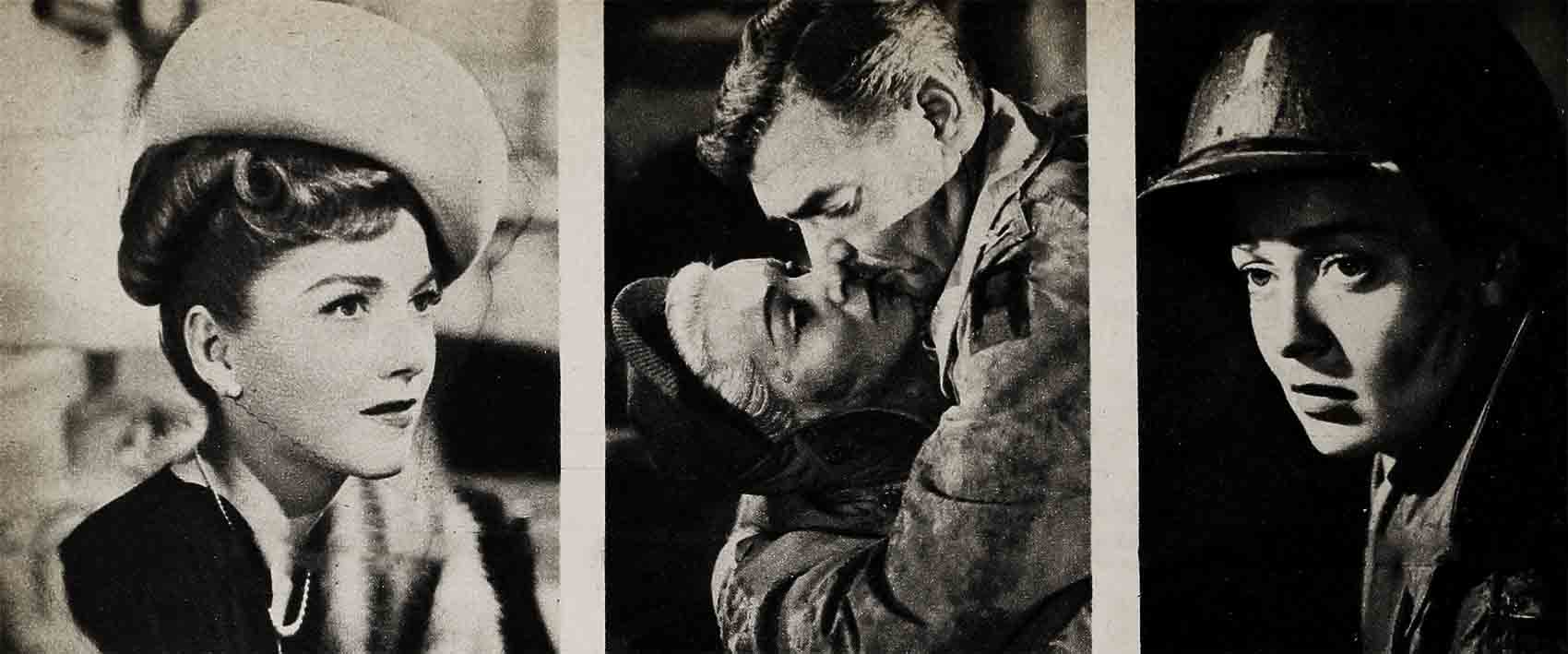

“HOMECOMING”

Produced by Sidney Franklin in association with Gottfried Reinhardt. Directed by Mervyn Le Roy. Screenplay by Paul Osborn from the original story by Sidney Kingsley, adapted by Jan Lustig.

With the following cast:

| Dr. Ulysses Johnson | CLARK GABLE |

| Lt. Jane “Snapshot” McCall | LANA TURNER |

| Penny Johnson | ANNE BAXTER |

| Dr. Robert Sunday | JOHN HODIAK |

| Dr. Avery Silver | RAY COLLINS |

| Sgt. Monkevicz | CAMERON MITCHELL |

| Sgt. McKeen | MARSHALL THOMPSON |

A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Picture

Silver didn’t have a chance to answer, not with that clear, scornful voice breaking in. “Wishful thinking,” she said and as Ulysses turned sharply he saw the girl half-sitting, half-lying beside him, her hands clasped behind her head, her eyes staring up at the stars. “Wishful thinking, just the way we got here.”

Ulysses shrugged and turned away. “I wonder what my wife’s doing now, this minute.”

Silver tamped down his pipe thoughtfully. “Mine’s just putting the kids to bed. You got any?”

“No,” Ulysses said. “Never felt the need for any.”

There was a rustling beside him as the girl straightened into a sitting position. “You don’t know what you’ve missed,” she said. “My boy is six now.”

“Really?” Ulysses glanced at her indifferently. “Then why are you here?”

“Because I want him to become twelve,” she said.

Ulysses lifted an eyebrow. “Where’s your husband?”

“Somewhere in China.” Her voice didn’t change at all. “He’s buried there.”

He shifted uncomfortably. “Oh,” he said. And then: “Sorry.”

“It was six years ago,” she said simply, “and anyway, he was fighting for what he believed in.”

“Fighting? In China?” Ulysses looked his bewilderment. “Was he Chinese?”

“No. He was an American pilot.”

Ulysses felt more bewildered than ever. “Why can’t people just stay home and live their own lives?” he sighed. “Enjoy the good things, their work, their homes . . .”

The sins short laugh came. “Comfortable philosophy, Major. You can’t understand it at all, can you? Why an American should be fighting in China?”

He flushed. “No, I can’t,” he said abruptly. “A man leaves his wife and child to fight in a war that was none of our business!”

“Wasn’t it?” she asked cryptically.

“Not six years ago,” he retorted.

She looked at him, then swung lightly to her feet. “My husband hated aggression even six years ago,” she said and his sense of discomfort heightened as she left her place on the deck.

“Of all the fresh . . .” he grumbled. “Who is she?”

“Snapshot, they call her.” Silver knocked the ash out of his pipe. “I think her name’s . . . let’s see . . . McCall. That’s it. Lieutenant McCall.”

“Whose nurse is she?” Ulysses asked. “Not yours, I hope.”

“No.” A faint glimmer of amusement tugged at Silver’s lips. “She’s yours.”

That was the first time he mentioned Snapshot in his letters to Penny, feeling some of his annoyance leave him as he wrote, the way exasperation always had a way of going when he talked things over with her. He gave the girl a wide berth for the rest of the trip and then forgot her. For it was Africa they’d been heading towards after all, coming in on D-Day directly after the first wave attacked Casablanca. There was plenty to keep the Medical busy then—so busy that Ulysses didn’t even recognize her at first as one of the nurses assisting him.

It was her amazing competence that made him notice her again. The attack on Kasserine Pass had begun then and he wouldn’t have known what to do without Snapshot during those nights and days. It was uncanny how she was always there, right when she was needed.

One night—it was really morning, for reveille sounded just after he reached his tent—he was so exhausted that he didn’t have the energy to begin undressing. As he sat on his cot, Snapshot suddenly appeared in the opening of his tent carrying two, mugs of coffee.

“Mind if I sit down a minute?” she said, and as he nodded, sank down on a chair facing him. “I was very rude to you that evening on the boat. I’m sorry.”

It was amazing how much it pleased him. “Well,” he grinned ruefully, “I can’t say as I blame you . . .”

“I’m a very irritating person,” she said.

“So am I,” he confessed. He looked at her and was amazed to see the color flooding her face. He’d never have put Snapshot down as a girl who blushed, even occasionally.

“If . . .” she said, “if . . . you’d want to be friends, I’d like it very much.”

He felt so relaxed, and it wasn’t just strong, hot coffee that made him feel that way, either. “You’re a funny kid, Snapshot,” he smiled. “Of course, I want to be friends.” He took another gulp of coffee. “Boy, is that good!”

“I hope it doesn’t keep you awake, Major,” she said.

“Too tired to sleep, anyway,” he answered, “and look, don’t you think we could dispense with this Major business?”

“What should I call you?” Her unexpected smile came, “I certainly can’t call you Ulysses.”

“I’ve had trouble with that myself,” he confessed. “All my life.”

“Perhaps I should call you what I’ve been calling you to myself, though lately I haven’t been sure it fits you. It . . . it’s Useless.”

It was amazing, but he didn’t mind. “Well, it could be worse,” he laughed. “Cigarette?”

“Thanks.” She took one out of the pack he held out to her, but as he reached for a lighter she had hers out first. As she flicked it open, the cover jarred loose and fell to the ground. “It’s always coming apart,” she said as he returned it to her. “It lights though.”

He wrote to Penny after she left, telling about the visit, and he must have betrayed more interest than he realized for when the answer came there wasn’t any doubt that Penny sounded jealous. Ulysses was in Anzio when the letter caught up with him and he laughed about it at first. But that was before he and Snapshot took the jeep and went out to take a swim in the ruin of an old Roman bath, with each of them standing guard while the other gave themselves the luxurious scrubbing down they’d been longing for, for days.

They’d had fun, but that wasn’t what changed things. It was after they were back at the base, he began to realize how important Snapshot had become to him. Some new cases had come in and Ulysses had been appalled when he recognized one of them as the boy who used to deliver the laundry back home. He had a ruptured spleen and nothing could be done about it because he had been bled white by hookworm. And not only that he had malaria, contracted long before he enlisted. Ulysses had a bad time with himself, knowing the boy had lived in a tenement in Chester Village.

Snapshot couldn’t hold back her indignation as they left. “Malaria, hookworm—doesn’t that make you laugh?” she said bitterly. “An American soldier killed on the field and not by the enemy! Imagine the kind of hole this kid had to live in at home. Weren’t ‘there any doctors around who knew what was going on, or didn’t they care enough to do anything about it?”

“Some doctors cared,” Ulysses said, “but I wasn’t one of them. He . . . he came from my home town. You’re right, Snapshot. I never cared enough.”

He knew then how much she meant to him, seeing the sudden sympathy on her face. “You’re a swell guy, Useless,” she said and the simple words were like a lifeline flung out to him.

It didn’t get any better as time went on. All through the months that followed he found his feeling for her growing, until sometimes it was all he could do not to tell her how he felt. They had come a long way from Anzio. There had been Rome and after that the invasion of France. Then had come Carentan, Saint Lo, Dumfront, Soisson, La Capelle. They were at Bastogne that time he knew Snapshot. too, had gone through her own little private war and Jost. A messenger came to him with a transfer to be signed and when he looked at it he saw it was made out in Snapshot’s name. He had been hurt at first, until he realized why she wanted to leave the outfit. On the day she was leaving—he couldn’t help it—he took her in his arms.

It was all right to show how he felt then, because he would never see her again. But it wasn’t goodbye after all, for a few days later when he was on leave in Paris there she was coming into the dining room of his hotel.

Time had given them a reprieve and they were together again. It was such a little time to be crowded with memories, walks in the clear, thin winter sunshine, hours spent talking, sometimes seriously, sometimes laughing at nothing at all, and the other times, the best times, when she was in his arms as they danced together. There was only one thing he could not tell her, the most important thing of all. that he loved her.

She was on leave, before her re-assignment to another group, and they thought they still had more than a week together when the news came that the Germans had broken through and Bastogne was surrounded.

Ulysses had to get back somehow. knowing how desperate the need for doctors would be. He commandeered a jeep and when it was ready, Snapshot was already sitting in it, waiting for him Looking at her face, he knew it would be useless to try to stop her from going with him.

They had almost reached Bastogne. taking wide detours along rocky little back roads, when they were suddenly caught in the crossfire of a tank battle There was a farmhouse a few yards away and they made a dash for it when a shell struck their jeep. But it didn’t seem any safer there in the cellar with the house crashing down above them. Only by a miracle would they ever leave that house alive.

He had to tell her then. He had to crawl to her over the mud floor and hold her. “Listen, Snapshot,” he had to shout to make himself heard. “whatever happens, whatever has happened in the past I’ve never been so close to realizing what life is all about, as in the time we’ve been together I love you. Snapshot.”

She clung to him then, and though she was crying a little, she was smiling, too “Oh, Useless!” she said And as he kissed her the smile was gone and only the tears remained. “Oh, darling, darling, darling,” she whispered and the words sounded like a prayer.

The mist was lifting now The statue was clearly visible and even the skyline was beginning to take shape. Ulysses took out a cigarette and as he lit it the cover of the lighter fell off and rolled down the deck. He stooped to retrieve it and the tears he had managed to hold back before smarted against his eyes.

But the tears were under control when he saw Penny Everything was under control, under the shell he had managed to build around himself again Home, everything about home. was so familiar and yet so strange The geraniums along the path, the logs blazing in the living-room fireplace and Penny with the happiness draining out of her eyes as he kissed her He hadn’t realized how far he had gone from her until his lips touched hers and it meant nothing nothing at all.

He thought it would be better when he got used to the idea of being home again But it didn’t get any better He was a man going through nothing but motions until that day he went down to Chester Village and saw Bob Sunday and after that the father of the boy who had died at Anzio.

It hadn’t been easy confessing the guilt that lay like a brand on his heart. But after the words were out, after he told hem that from then on he was going to be in the fight that had been going on down there, it was strange how the other thought came, the certainty that Penny would help him.

That evening he found he could talk to her, really talk to her for the first time since his return “Penny.” he said, “remember how when I left we promised each other we wouldn’t change? Well, I’m afraid I’ve broken our bargain I feel different about things I’ve lost some of the assurance I used to have and yet in another way I feel surer than I ever did before I can’t really explain.”

“You don’t have to explain.” she said quietly and her voice didn’t change at all as she went on “Lieutenant McCall has she come home too?”

“She died,” he said.

“Oh! Penny looked as it something froze inside her and as she went on he knew the effort it cost her “Would you like to tell me about it?”

“Yes. Penny, I would,” he said “I’d like to very much Maybe it would be easier for you if I didn’t, but I couldn’t go on living with this inside of me. without your sharing it. And if you can only bear with me for a while.

She looked at him and her eyes weren’t frozen any more They filled with tears as she came over and sat on the sofa beside him. “I wonder if you know,” she said, “what it meant to me when you left, being the one who was left out, the one who did nothing. In all these three years, that was the worst of it, that I couldn’t be near you, do things for you, share your life. My only hope was that when you came back you might need me. And now, you do need me, Lee! I’m in it again. You ask me if I can bear with you for awhile! Oh, darling, I can bear with you for as long as our lives last I love you, Lee.”

She didn’t kiss him. Instead she took his hand and held it as he talked. Somehow it wasn’t hard telling her the way he had thought it would be. Not with his heart slowly beginning to live again in the quiet joy of knowing he was home again, really home, at long last.

THE END

—BY ELIZABETH B. PETERSEN

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE JULY 1948