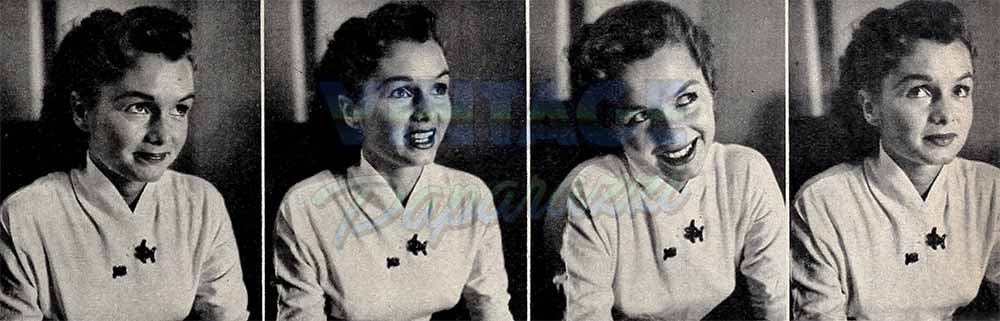

Split Personality

“Come on, drink it. Don’t be snooty, or your old mother’ll hit you in the head,” said Debbie, addressing her dog. She shoved a bowl of water under its nose, and tied it to the chair-leg with a rope. “Because those old leashes cost so much,” she explained the rope. “Imagine, three dollars for a .collar, three for a leash. Practically my whole allowance, and she chews it up. Let her chew rope, which doesn’t cost a thing. It’s the studio’s rope.”

The poodle dunked a paw into the bowl. Debbie bent down and quickly undunked it. “Now you’re going to catch pneumonia or something—and who’s got time to soothe your foolish brow? Settle down, thing.”

The pup settled. So did Debbie. She’d been rehears- ing dance routines for the Marge and Gower Champion musical, “Give a Girl a Break” and this was her lunch hour. A sandwich in one hand, a mammoth carrot in the other punctuated her discourse. Through the sunlit strip between sound stages, people came and went. At times she’d tip her carrot in salute. At times she’d be too deep in talk to notice. It made no difference. Sighting the green-eyed elf in the canvas chair, each face cracked into a wide warm grin.

Meet Miss Reynolds and you’re meeting a pair of characters. One’s the kid Gene Kelly was talking about when he said: “There’s nobody younger than Debbie. Not even my daughter and she’s nine.” The other’s a twenty-year-old, whose maturity of outlook would do credit to many of her elders. Debbie the First chews gum with abandon, pines for a monkey ’round the house and greets star-stuff with, “Hi, glamour boy, I say that laughingly.” Debbie the Second hates being called wonderful. “I never believe a person when they tell me stuff like that. It’s too much praise. Anything too much is no good.”

The two Misses Reynolds make a combination as natural as a mountain spring and equally refreshing. Words tumble from her in a rainbow stream of gaiety, yet they are laced with common sense. It’s not her wit that endears her to people, but her spontaneity. Unselfconscious as a puppy, she wouldn’t know a complex if it brought a letter from Freud. Given the chance, she’d flop on her stomach with a queen and dish as cozily as with a girl friend. She can’t understand being ill at ease with people. “You are what you are, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Only on one occasion did the cat get her tongue. Standing outside the studio commissary, ali of a sudden without any preparation, there was Clark Gable. “Hello, Debbie,” he said, and she fell on the floor.

With Gene Kelly, talking presented no problem. She merely couldn’t dance in front of him which, considering the script of “Singin’ in the Rain,” made everything great. He’d show her the step. She’d look on like a goon. “Try it,” he’d say. Her legs would refuse to budge. “You’re on a pedestal,” she’d wail, “and I’m in the soup.”

“Let’s meet halfway.”

She’d had no professional training. Kelly and O’Connor were both tremendous hoofers. “Just the same,” she recalls severely, “I acted real young. But Gene had more patience than Job, so I gradually aged.”

The wrinkles don’t show yet and she’s still comparatively carefree, despite an impossible schedule that keeps her tearing around from pictures to publicity. from tap and ballet to voice and dramatic lessons. She loves the whole business now, though when Warner Brothers first signed her, it was just a joke to sixteen-year-old Mary Frances, and at times a poor one. Her heart belonged to John Burroughs High, to the Girl Scouts, to the French horn she tootled in the band, and to umpteen other activities. It belonged to her studies, too. She worked hard for good credits, so she could get to college and be a gym teacher.

Then came the Burbank on Parade con- test. Debbie practically passed out when the emcee announced, “And Queen of all Burbank, Miss Mary Frances Reynolds.”

As per agreement, Warners handed her a contract, but no work till the very end when she played June Haver’s sister in “The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady.” The awful part was dropping out of the beautiful hurlyburly of Burroughs. Mornings she went to school at the studio, afternoons she tried returning to her own bailiwick, and she learned firsthand of the perils of prominence. Lots of the kids expected her to be snooty, so they beat her to the punch by being snooty first. She’d trail home and cry like mad, which relieved her emotions, but failed to solve the dilemma. She advised herself, (1) Cheer up; (2) Steer clear of Burroughs till your contract runs out, then go back and forget the whole dumb deal, including Deborah.

That’s the name they picked for her, Deborah. “What’s wrong with Mary Frances?”

“Too plain. What’s wrong with Deborah?”

“Too dignified.”

They compromised on Debbie. But to her family and school friends, she remains Franny. To herself, she’s a split personality. “I feel like Franny at home and like Debbie on the lot, and you’d be surprised how the two of us get along.”

Burroughs she had to get along without. M-G-M caught her when Warners dropped her option. “Two Weeks With Love” did the trick. Most beginners (and some veterans) will tell you they writhe in torment through their own performances. Such is their agony that they skulk into darkened theatres to suffer alone. Debbie’s the exception. In addition to parents, grandparents, brother Bill and his wife, Joyce, she rounded up twenty of her gang for the sneak preview. If they liked it, fine. If not, the world would still turn. Watching herself on the screen, she felt no pain. Out of her first bout with autograph hounds she got the topsyturviest feeling. “They acted like I was doing them a favor. Golly, imagine what they were doing for me!” After a malt with her girl friends, she went home to her folks who never dreamed of calling her wonderful. They liked her, that’s all. Bill said, “Pretty good, Sis.” She doesn’t remember what anyone else said. As Mary Frances, Bill’s “pretty good” had always been her private Academy Award. It was good enough for Debbie.

The picture started Debbie’s stock soaring and her mind working. Up to then, it had all been an accident, pleasant but crazy —and likely to explode in her face any day. Up to then, none of it mattered much. But suddenly it came to matter a lot. “You know that old corny saying about grease- paint getting inside of you? Well, it’s inside of me,” she informed her parents.

On the subject of her mother and father, she’s not effusive. She just talks about them, and soon it becomes plain that no parents were ever more popular with a child. “They’re immensely broadminded. Not knowing a thing about show business, all of a sudden here I am in the midst of it. Many others would likely be inclined to say, ‘We don’t think our daughter ought to go into it. This is supposed to be quite a fast business. She might change.’ What they did, without telling me till much later, was just quietly take themselves over to Warner Brothers, and meet practically everybody except Jack Warner. There’s nothing at all wrong with these people, they decided. They’re pretty nice folks—and you can be just as fast in whatever business, if that’s how you feel about it. So when I said I wanted to stay in, it was fine with them.”

For the rest, she feels very lucky, but keeps a temperate head. “I don’t burst with excitement. I’m not demonstrative that way. Maybe it’s better when you are. It makes people think you appreciate it more. I couldn’t appreciate it more, but I can’t go around screaming about it and I’ll tell you something: If a fairy godmother had tipped her wand and asked me to choose, I would have liked finishing high school first. High school’s such an unworried kind of fun. This is a real responsible kind of fun. Please don’t make it sound like complaining. It’s just a small regret.”

The family now includes Joyce and baby Gail—Bill’s at Fort Ord—and they all live together in the house Dad bought when they left El Paso for Burbank twelve years ago. Since Burbank’s a long haul from the studio, Debbie’s sometimes asked why she didn’t take a place of her own. This query never ceases to puzzle her. “What for? I’d be embarrassed even to mention it. It’s like saying your parents’ house isn’t good enough. I love their house. I wouldn’t want to live anyplace else. It’s not the size that makes a home, but the spirit. In size, it has bedrooms enough for all of us. In spirit, it says, ‘Come in and bring your friends and take your shoes off.’ ”

Dad works for the Southern Pacific. Mother’s a housewife. They live on his salary, as always. Debbie’s business manager invests her earnings, and gives her twenty a week to squander. “That goes for lunches, bowling, shows, and if I want to buy a belt or something. Right now the family’s away, so I have to spend more for food. And my deg, Tourjete (named after a ballet step) and cat, Henry, eat better than I do.”

Living at home doesn’t cramp her sense of independence, an asset diligently fostered by her elders. In her three years at M-G-M, Dad’s never been seen on the lot, and Mother rarely. “You wouldn’t believe it,” she reported to Mom one day, “but some mothers stick with the girl. This would be to me very disconcerting. It would wear me out.”

“Wear you out? And what on earth do you think it would do to me? I don’t have to follow you, Franny. You’ve been raised so we know you won’t go off your rocker.”

She’s been working too constantly to enjoy much leisure. Even on Sundays, she poses for magazine layouts. But when a holiday does come along, her idea of fun is to sleep late, have a girl friend or two over, swim and lie in the sun with the radio on. Evenings she gets in around seven, eats, helps with the dishes, plays records, reads and goes to bed.

She thinks it’s wrong to let movies push all the rest of life out of your head, and make you one-sided. In her family, you can’t be one-sided, because they’re interested in too many other things. With Dad, she has big discussions about politics and what she calls “worldly situations.” Mom’s community-minded, active in Scouting and the local Blood Bank. If Mom fails to get her quota, it upsets her to where she can’t eat or sleep. It upsets them all. Anything to do with Korea is their vital concern, not only because Bill’s at Fort Ord, but because lots of boys they know and don’t know are at the fighting front. Apathy on this score stirs Debbie to battle. “Some people know there’s a war on, but not with their hearts. They say, ‘Yes, it’s terrible,’ but ask them for a pint of blood they’ll never miss and some kid might die without it, and they drift away.” The green eyes cloud. “I don’t know if it makes me mad or sad.”

She used to get mad with the greatest of ease. Time was when she’d holler and claw and hit, or stomp off in a rage when they called a foul on her. Somewhere in junior high she got wise to herself. Said Debbie to Debbie: “You’re being pretty childish, letting yourself blow your top on purpose about stuff you won’t even remember tomorrow. Better change your ways, sister.” And she did.

Both at home and studio, she’s predisposed in favor of the human race, though some members of it, like habitual late- comers, drive her nuts. And she has no use for people who pretend. She can always spot them. “Because they’re too, too sweet or too, too something.” According to Mother, one of her main faults is how she treats the few who get on her nerves. “I find it hard not to be really sarcastic. I do all I possibly can to antagonize them. I usually succeed.” Mother believes in politeness, no matter how you feel. So does Debbie, in theory.

Debbie’s dream-come-true is her swimming pool. They joked about it at home, knowing they’d never be able to afford it. But after her contract, the joke turned into the dream, and the dream came closer when her manager said she had enough money in the bank. Dad was against it, however. He doesn’t like you to change things round the house. So she went to work on him. Not in a crude way, not nagging, “Dad, please can I have a pool?” Very subtly. Say they’d be mowing the lawn on a hot afternoon, and she’d push the damp hair from her brow, heave a heartrending sigh over all the grass left to be cut, and watch him weaken out of the corner of her eye. By the time he left for his vacation, she saw he was weak enough to stand the shock. “So home he comes and finds this big enormous hole in the ground. My poor father just looked at it. Then he said that what’s done is done, which has always been his philosophy. But on top of that he likes swimming.”

When it came to her room, she asked the question direct. “Pop, can I make my room bigger?”

“What for?”

“My clothes. They’re spilling over.”

“Can’t be done, Franny. It means changing the roof.”

As a practical psychologist, Franny’s no dope. Before departing on a personal appearance tour, she carefully arranged garments every which way over bed, tables and chairs, achieving an effect of orderly disorder. She figured her father’d wander into the room. She figured he’d miss her. She figured his heart would be smitten for his poor absent daughter without enough space in her home to hang up her clothes, though she did her pathetic best. She figured right. On her first night back Dad produced a paper. “About your room, honey. I called in some men and got some estimates. Let’s sit down and see who can build it the best for the least.”

When it was completed, Mother sectioned off the cabinet for her monkey collection, so that each monkey has its own little nook. Her delight in monkeys dates from her earliest visits to the zoo. Dolls she never cared for, though she’s kept about seven for her children, in case there’s a girl and she’s silly enough to prefer dolls to monkeys. Her thwarted ambition is to own a live one. Whenever she mentions it, the roof comes off. “Dogs, cats, I don’t mind,’’ says Mom. “But monkeys, no!”

“Then I’ll just have to warn my husband.”

“What husband?”

“The one I won’t marry unless he gives me a monkey.”

But at the moment, marriage is some- thing she thinks of as way off in the future. Bob Wagner—universally known as R. J.— is the boy she dates most, which doesn’t mean they’re exclusive with each other. She enjoys going out but not to the point of overdoing it. For one thing she works too hard. For another, she is a sleepyhead and ’round eleven she gets tired.

R. J. understands Debbie perfectly. He’s a most considerate person. If you’re dead beat and beg off a date, he never gives you a sarcastic routine. He says, “Get a good night’s rest. I’ll call you next week.”

R. J. doesn’t try to change her, doesn’t think her monkey collection’s idiotic, doesn’t poke fun at Scouting. “I don’t have time to be active in it now, but I’m vitally interested. Some people think if you’re in the Girl Scouts, you have to be this small, smaller than Tourjete, or Henry. They think when you’re grown up, it’s the stupidest thing which, if you’ll pardon me, is pure ignorance. R. J. kids me about it, but in a sympathetic way, and that’s different. I’m completely myself with him, for better or worse, and I don’t mean the marriage service. I just mean friendship.”

Marriage is like a career, Debbie believes. It takes lots of time. To be fair all round, a girl should either have her career well set or else no career. Janie Powell was set. So was Liz Taylor. Debbie’s just building up what they’ve had seven years to accomplish. “I was thinking about it the other night. How I dash out of bed in the morning, work all day, then barely have time to rush home and hit the sack. Heavens-to-Betsy, my poor husband would never even see me.”

A messenger came to call her back to rehearsal. Hoisting her poodle under one arm and her thermos under the other, she flitted off like a sunbeam in pedal-pushers, leaving the alley a little drabber. Which remark, being too, too sentimental, will doubtless annoy the heck out of her. So maybe we’d better take a leaf out of brother Bill’s book. As a performer, he dubbed her pretty good. As a girl, she’s likewise.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1953

No Comments