The Love Story of Deborah Kerr and Tony Bartley

This isn’t my own love story—which I really prefer above all others—but it comes next. And, if I weren’t slightly prejudiced, it would come first. I hasten to add that it happened before I met, wooed and won—which still amazes me—my wife, Jean Simmons. That taught me a lot of things.

In mid-winter of 1945, I was in England, busy with picture-making, and going out with companies to entertain the troops. Romantically, I was as blind as a bat. In fact, I was inclined to think that so far as actors and actresses were concerned, they were, by the nature of their profession, so busy making love on the stage that they couldn’t be serious about real romance.

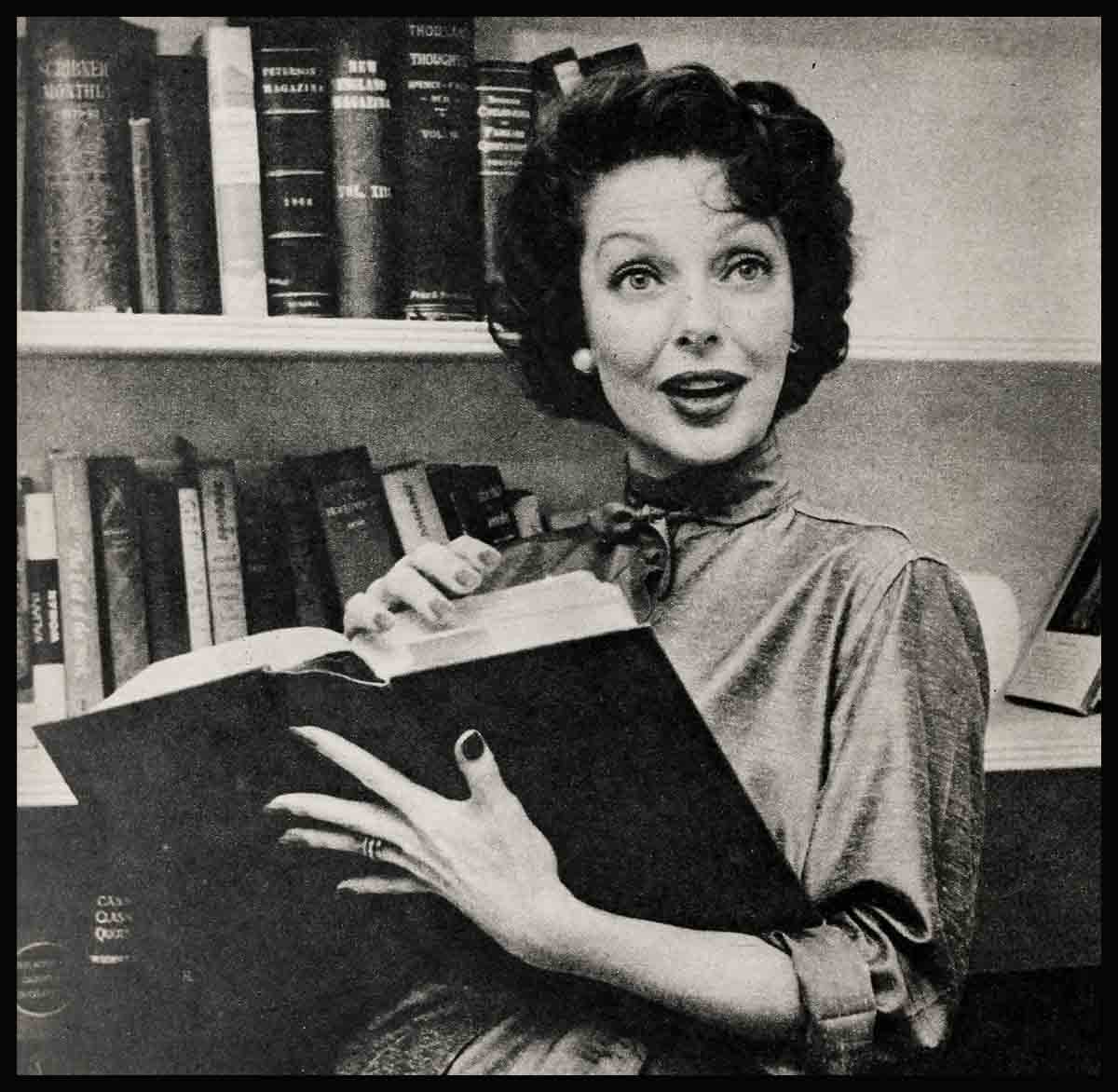

AUDIO BOOK

Among my friends were two people whom I greatly admired. One was Deborah Kerr, whose gifts as an actress are as great as her own charm. We had met in London in 1943, when I worked with her in rehearsals for “Heartbreak House,” her first West End play. I was pulled out of the cast for a picture before opening night and she went on to do the play with Robert Donat as her co-star. But we kept in touch and were good friends.

The other person was Tony Bartley. Now do you see where this story is heading?

I had known Tony during my own war service days. I knew, as everyone in England knew, the legend of the Biggin’ Hill Boys—a squadron of Spitfire pilots, commanded by Tony, who, in the terrible days when the Nazis were poised just across the channel, hurled themselves against the best the Luftwaffe could’ send and saved England.

Tony had joined the Royal Air Force when he was nineteen. His whole adult life had been spent flying. In the RAF he was tops.

Well, in the fail of 1945, Deborah and I headed a troupe to entertain the troops on the Continent with a production of “Gaslight.” It was the first time we had actually worked together.

Our first-night audience in Brussels was fresh from the battle front, eager for entertainment, and, to put it mildly, noisy. We loved every minute of the way they welcomed us, but when the final curtain went down, we were a tired lot of actors. We looked forward to getting back to the comparative quiet of our headquarters.

When I got back to my dressing room, I found a visitor waiting for me. His uniform was splattered with battle ribbons and his face was adorned with a scowl that made him look like a bushel of bulldogs. It was Tony Bartley. I hadn’t seen him for months. He was furious.

He had been grounded—to hear him tell it, the brass had personally and forcibly yanked him out of his cockpit. Ali be- cause he had flown a mere 1,000 combat hours. And hat-in-the-name-of-this-and-that was a man to do, in war-time Brussels, of all places?

Tony was reaching his peak when there was a tap at the door and Deborah looked in. The jeep was ready to take us back to the clubhouse. I beckoned her in. “I have an Air Force type here who’s feeling a bit low,” I said. “Can’t we take him back to supper at the club?”

I thought, in my bright-eyed innocence, that what Tony needed was an hour or so with a lively crowd to take his mind off his troubles. I looked around at him—and blinked. His scowl was gone. He was smiling and alert. He looked as if he thought Brussels were the most delightful place in the world. He said he knew a “gay little place” where he would like to take us for supper.

“I’m afraid Miss Kerr is a bit fagged . . .” I began.

But Miss Kerr never felt better, nor hungrier, nor more like seeking out a “gay little place.” She said so herself.

After a very long and very gay evening old-blind-bat-Granger earnestly thanked Deborah for being so sweet and kind to a poor lonely chap with troubles. I think I even used the word “motherly.”

Nonsense, she had enjoyed it, she said. And she added: “He’s sweet and he doesn’t look at all like a murderous fighter.”

And still I didn’t catch on.

Our troupe spent a week in Brussels and every day Tony and Deborah and I were out shopping, sight-seeing, going places and doing things. They didn’t ask me to please go away somewhere and get lost, and it never occurred to me.

The “Gaslight” company next went to Eindhoven, recently bombed and terribly depressing. There we found an Air Force fellow with a message from Tony. If we wanted any eggs Tony wanted us to know, he had a friend, a farmer, nearby. He was thinking of us, he added, and Brussels was deadly without us. Us! And eggs!

From Eindhoven we went to Lille and then back to Brussels at which Deborah seemed strangely pleased. In Brussels, Tony was waiting—but not for us. I was quite surprised. They started going out together after every performance, but somehow I wasn’t asked. It seemed a bit odd.

It as several weeks later, back in London, that the truth finally hit Granger over the head. Deborah and I were back at work in films, and I read over my morning tea a gossipy item in the Times to the effect that Commander Tony Bartley, his leave drawing to a close, seemed rather loathe to leave London. That seemed more than odd to me. Tony not anxious to get back into the air? It didn’t make sense. The next sentence opened my eyes. The reason, the item went on, was his blazing romance with screen star Deborah Kerr.

I called Deborah at once. “Is this true?” I demanded.

“Well, yes . . .” she temporized. “I think we’re engaged. . . .”

I had supper with the two of them once after that. But this time it was not as it had been in Brussels, gay and carefree. The long arm of war had touched them again. Tony was being shipped to the States and from there to the South Pacific.

For months, all her friends suffered with Deborah. There was almost no news. But at any rate, there was no bad news. That was about all that could be said. Then she telephoned in great excitement. Tony had a ten-day leave. He was going to hitch a ride on a transport plane and fly home by way of Ceylon. What with engine troubles, monsoons and a few other delays, Tony finally came roaring into London just one day before his leave expired. Time for a marriage, even if no time for a honeymoon.

And so they were married, with all Tony’s old squadron on hand. And Granger—if anybody cares—on location, sitting on top of a mountain in North Wales, waiting for the rain to stop.

The end of the war erased one hazard. Tony was safe. But it left another. All he knew was flying and most of what he knew was war. What could such a man do in peacetime? The answer seemed to be an off er from Vickers Armstrong Aircraft in India. But his wife was a film actress in England. The old story of one marriage and two careers.

They found the intelligent solution. Tony went to India. Deborah stayed in London. Then Deborah received a magnificent offer from M-G-M in Hollywood. She anted terribly to go, but she wouldn’t go without Tony. So he went to America, too, and faced another crisis.

Here on a visitor’s visa, he couldn’t even try to find work in America. He didn’t want to be just Mr. Deborah Kerr. And she didn’t want him to. She watched for a chance to help him. It came in hen Metro assigned her to star in “King Solomon’s Mines.” That brought Granger back into the story, incidentally, if only as a firsthand witness. We ere to co-star.

Doing “Solomon” meant going to Africa.

Deborah, very sweetly and firmly, issued an ultimatum. She would love to do the picture, but she couldn’t consider going to Africa without her husband. And since he, in America on a visitor’s permit, couldn’t get back once he had left, why. . . .

That did it. M-G-M bigwigs did some fast work, and a bill as rushed through the House of Representatives which took Tony off the uncertain status of a visitor and, according to its sponsor, as proper recognition for “one of our greatest allies’ greatest heroes.”

I spent five and a half months in Africa with Tony and Deborah and since then Deborah and I have made to films together. Although I had known the Bartleys ell before, I found that I had only dimly sensed the meaning of hat a marriage could be.

I know no that I as a privileged character to tag along during the beginning and growth of their love story, although it was a while before it dawned upon me that I as Cupid.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1953

AUDIO BOOK

Filomena Pernell

19 Nisan 2023Good write-up. I certainly love this website. Keep it up!