The Heart Never Betrays—Marlon Brando & Anna Kashfi

It is ironic that the things Marlon Brando regards as most intensely personal have been made most shockingly public. With the lone exception of Garbo, never has there been a star who strove so bitterly to keep his private life from the prying eyes of the press. Yet the most intimate events of his life have been exposed in screaming headlines—and it has been, on the whole, his own doing.

Didn’t he realize, when he became engaged to Josanne Mariani-Berenger, that his choice of an unknown French girl would provide a field day for the press? And whether or not he knew—or cared—about the story of Anna Kashfi’s mixed-up parentage, the fact remains it invited a deluge of the personal publicity he detests so much.

It seems as if Marlon’s heart has betrayed him. But has it? For the sensational, gleeful reports of his critics and detractors—as if they were sitting back, laughing, with fingers pointing, saying, “See! If you hadn’t been so stuck up we would have let you off easier”—tell only a fragment of the story. A story that, in justice to the sensitive, greatly misunderstood person Marlon Brando is, should be told. A story of his search for what he has called, “The only reason for living.” A search for love.

It began—as it does for everyone—on the day when he was born, April 3, 1924, in Omaha, Nebraska. Marlon’s father, Marlon, Sr., was the solid, successful president of Chemical Food Products Company, a Chicago concern manufacturing animal feed and fertilizers. His mother, Dorothy Pennebaker Brando, was a lovely, sometime-actress with great sensitivity and enthusiasm for all the arts, in whom her son found an understanding response to his own artistic leanings. His older sisters, Jocelyn and Frances, were fine playmates. (“I could beat him at football because I was bigger,” says Frances, “but he always got the best of me by making terrible faces.”) Both girls shared the artistic flair, too—Jocelyn is an actress, Frances paints. But there the re- semblance ends. The girls grew up, married happily, and became mothers in the conventional pattern that might have been predicted from their background.

From the beginning, Marlon was marked with a need and a feeling for others that went far beyond the family circle. From earliest childhood, he had an un-usual compassion and affection for all living things. Once, when he was very small, his pet chicken died. When his mother buried it, he dug it up and brought it back into the house. She buried it again—and Marlon dug it up again. This went on until his mother put her foot down.

He brought home all kinds of stray animals, usually in some sick stage, and cared for them lovingly, whether a stricken snake, a wounded bird, or a mangy cat. Later, when he reached the dating age, “He always picked the cross-eyed girls,” his grandmother remembers.

What happens to such a boy when he becomes a man and begins to seek, in the large world outside Libertyville, Ohio, fulfillment for that great need to love, not only in simple, personal terms, but in the largest humanitarian sense?

Those who know him well believe that the search really began in the summer of 1953. At that point, Marlon Brando was a man emotionally torn. One great conflict—that of winning approval of his businessman father or his ailing, artistic mother—had caused him many pangs in his struggling days. But with his success as an actor, it was resolved. (He keeps his Oscar for “Waterfront” beneath his mother’s portrait—she died before he won it; his father is now his closest business associate, confidante, and friend.) But the conflict of Brando versus others had just begun.

Now the object of world-wide fame, he tried violently to hold onto the relationships of the past, with all their simplicity and privacy. And in the summer of 1953, he found how impossible that was and how impossible for him to find happiness in the simple, easy way it comes to others.

It was the summer of 1953, when he was already established as a Hollywood star, he could have commanded an enormous salary for his efforts. Instead, he chose to tour the summer circuit with a “package” show of George Bernard Shaw’s “Arms and the Man,” so that some of his closest friends who had not been as fortunate as he in becoming a success would be able to have work in the theater. That summer, Marlon knew he was a star. That summer, he was surrounded by his friends. And so, according to the rules of what every young actor should have, Marlon should have been happy. But at parties, at small gatherings, with only his closest friends present, Marlon would be restless, the gaiety which used to show itself with these friends had seemingly disappeared. Even with close friend Wally Cox, who was touring the summer theaters at the same time, only occasional spurts of that dry, whimsical humor which used to pass between the two friends would show. “Marlon needs to fall in love,” one of his friends had said.

Dissatisfaction seemed to plague Marlon all that summer. Some attributed the feeling of heaviness to Marlon’s disappointment with his return to the legitimate stage. It was the stage that had started him, and the stage to which he supposedly wanted to return: He had sneered at Hollywood from the beginning, saying the only real place for artistic endeavor was the theater; and yet his return to the theater was greeted with a tepid reaction by audience and critics alike. “Marlon will never do another play after this summer farce,” one of his friends said. “If there’s one thing he’s afraid of, it’s rejection, and he’d never go back to Broadway if he thought they’d greet him the way they did in this play.” But the somber, uncomical ambiance of the production was explained differently by another friend, and more accurately: “There’s only one thing wrong with this play,” she said. “The whole company’s in love with the leading man.”

This wholesale adoration can be very confusing and very unsatisfactory to a young man who feels a desperate need for love. The love of many cannot substitute for the love of one person.

After that summer, it seemed that Marlon had perhaps found the one person, in Movita Castenada, the dark long-haired, fiery but mature Mexican actress. The fact that she was several years older than Marlon served only to enhance the relationship, as Marlon adored his mother, and felt in this woman the maturity and gentleness that seemed to be lacking in the younger girls he dated. Another attraction for him was her European-style upbringing: To the European woman, her man is the center of the universe, and she concentrates her attention and affection on the object of her love the way Marlon felt no American woman could. “Marlon thinks American girls are too emancipated,” his friend said. “It seems as though the only area where they act like women is having babies, and if there was any way they could make the guys do that instead of them, they’d do it. But Movita’s different. There’s nothing she won’t do for Bud, but she’s still got a mind of her own, so it’s not as if he was the feudal Lord, and she was just a silly handmaiden. She’s just what he needs.”

And perhaps she was, at the time. But in spite of the fact that he now had a single love, instead of the love of many, Marlon could not sacrifice that “wholesale adoration” of his friends. He had always taken time to get to know someone, to decide if it was worth becoming his friend. But once he had admitted someone to his “inner circle,” he felt the act of friendship had to be an active thing, and that it was impossible to deny anything to one of the people he cared about, even to say “I’m busy.” In the beginning, Movita tried to understand and accept the many people about them. But after a while, it became increasingly difficult for him. She had hardly any time with him to herself.

“I remember one night,” one of the group said. “A bunch of us went up to Mar’s and Movita was there cooking dinner for him. You could sort of tell that she had planned it to be something special—she made a complicated Mexican dish, and there was only enough for two. Mar insisted that she split up his portion among the rest of us, and for a minute I didn’t know whether she was going to hit him with that big frying pan or burst into tears. But he gave her one of those famous looks, and she said something quick to herself in Spanish, and everything was all right. But she came over and made sure he ate every bite of her portion.”

How many nights like this there were, it would be impossible to say, but Movita moved out of his life, the parting telling him she needed to be a woman as well as a mother, and Marlon, with an ironic smile, said if he had to choose between her and his raccoon, he would pick the raccoon.

It was almost as if Marlon was trying to prove that he had no need for a woman who was a mother to him, when he found Josianne Mariani-Berenger: for Josianne was, essentially, the very pole opposite to Movita. Child-like, frail, and with an impish quality, Josianne radiated naiveté and youthful wonder. Like Movita, she was dark and European, but there the resemblance ended. Josianne had met a psychiatrist and his wife in France, and they had persuaded her to come to New York to act as governess and teach French to their children. Once in New York, Josianne began taking acting lessons from Stella Adler, Brando’s former teacher. It was at one of Stella Adler’s parties that they met, and Marlon was immediately struck by the tiny, completely feminine girl with the big black eyes. He could speak to her in French (his name was originally Brandeau), and he could talk for hours on end of his ideas of philosophy, and morés, and Josianne would sit for hours on end, watching him adoringly with those wide, dark eyes. “He needs to know that he’s something: He wants someone he can teach and talk to who won’t bring him down,” another friend remarked. “Josianne is like that; it’s a fresh mind, like a new page. He doesn’t want to have to prove anything anymore, like he did with Movita. He wants to be accepted as wonderful from the very beginning.” And he was.

When Josianne returned to France for a visit with her parents, Marlon followed. He spent two weeks in Paris, staying at the apartment of Movita’s friend, Maria Felix, who was in Mexico making a picture. And yet the two weeks in Paris showed no sign of the former “Enfant Terrible,” as the French called him. He was not seen in leather jackets, on motorcycles, even in a city where motorcycles are a more common occurrence than automobiles. And at the end of two weeks, he had made up his mind. The engagement was announced, and a seemingly content Marlon, with a radiant Josianne, came back to America.

Once back in this country however, the old pattern of indecision began to show itself. They frequented Marlon’s favorite haunts, The Russian Tea Room, the Carnegie Tavern, and he thought he was, and seemed to be, very much in love. But the prying eyes of the people made Marlon uncomfortable, and they could not go to the places Marlon liked to go with Josianne, the places where her child-like enthusiasm for life could be shared by him; where they could have fun: amusement parks, open-air concerts. Too many people recognized him in these places, and so Peter Pan and his French Wendy had their wings cut off, and were forced to meet in dark corners. And gradually the old restlessness reappeared: Marlon went to California to make a picture, and Josianne got a modeling job in New York, confident that he would send for her when he was ready to get married.

Marlon has been quoted as saying: “She has some growing up to do,” about Josianne. And there would seem to be evidence that he was absolutely right: Only the very young and very innocent can be as sure as Josianne was, that nothing, and no one could come between their love. When the young blonde German actress, Ursula Andress met Josianne in New York, and they became friends, Ursula told Josianne that she was going to Hollywood, and Josianne suggested that Ursula contact Marlon when she got there. Ursula did contact him and soon the rumors began filtering back to Josianne that Marlon seemed to be showing more than a friendly interest to the newcomer. But Josianne merely shrugged and smiled and said: “It will pass. I blame no one.” Ursula went on to date Jimmy Dean, and later to marry John Derek. And when Josianne arrived in California she was as friendly with Ursula as she had ever been, confident that her faith was justified.

“Isn’t it remarkable,” one of Marlon’s earlier girlfriends said. “There isn’t a girl anywhere in the world who has ever had anything to do with Marlon who doesn’t blame any problems she has on him. And there isn’t a girl anywhere in the world who wouldn’t be waiting for him if he ever decided to come back.”

And as for Marlon’s seemingly constant flirtations with Rita Moreno, etc., Josianne realized that she had fallen in love with a quicksilver and tempestuous young man, who was attracted by dark beauty, and who was not yet ready to take root. And Marlon himself laughed about girls in general, and joked with his ever-present friends about how silly most of them were.

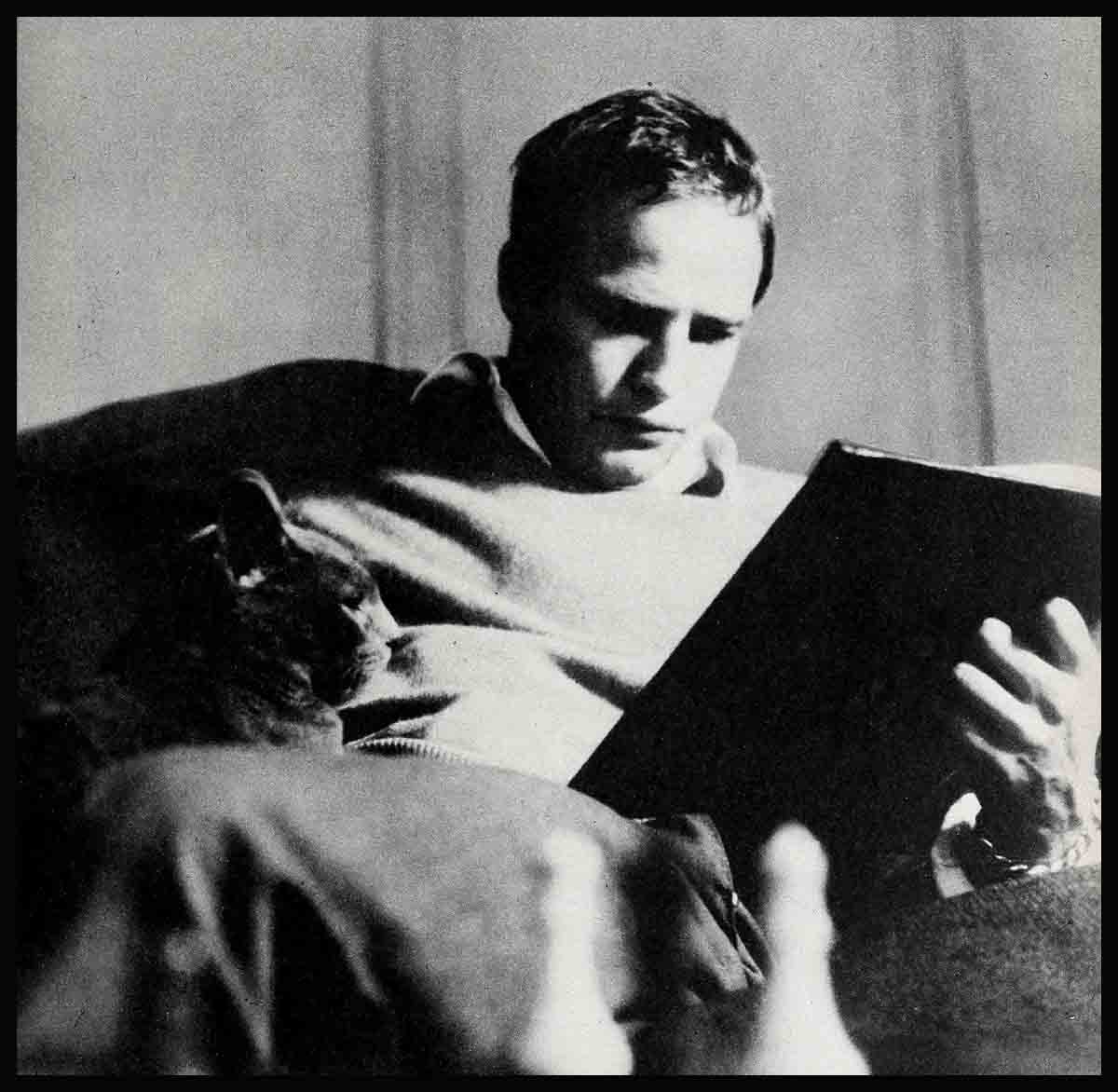

Then something totally unexpected happened. Marlon had, ever since going to Japan for location shots for “Teahouse of the August Moon,” become fascinated with the culture and the philosophy of the East. Marlon himself has declared that he never reads fiction, and this seems to be not so much a scholarly snobbism as it is the need for a young man who, because of lack of discipline and rebellion, never completed his formal education, and wants desperately to think, not just as ordinary people think, but as the great minds do. So he devours tomes of philosophy and intellectual discourse, in order to become his own most respected object: the truly intellectual man. But in the literature and the religion of the East, and the way of life, he seemed to find a wisdom more secure, more lasting, than any he had ever encountered.

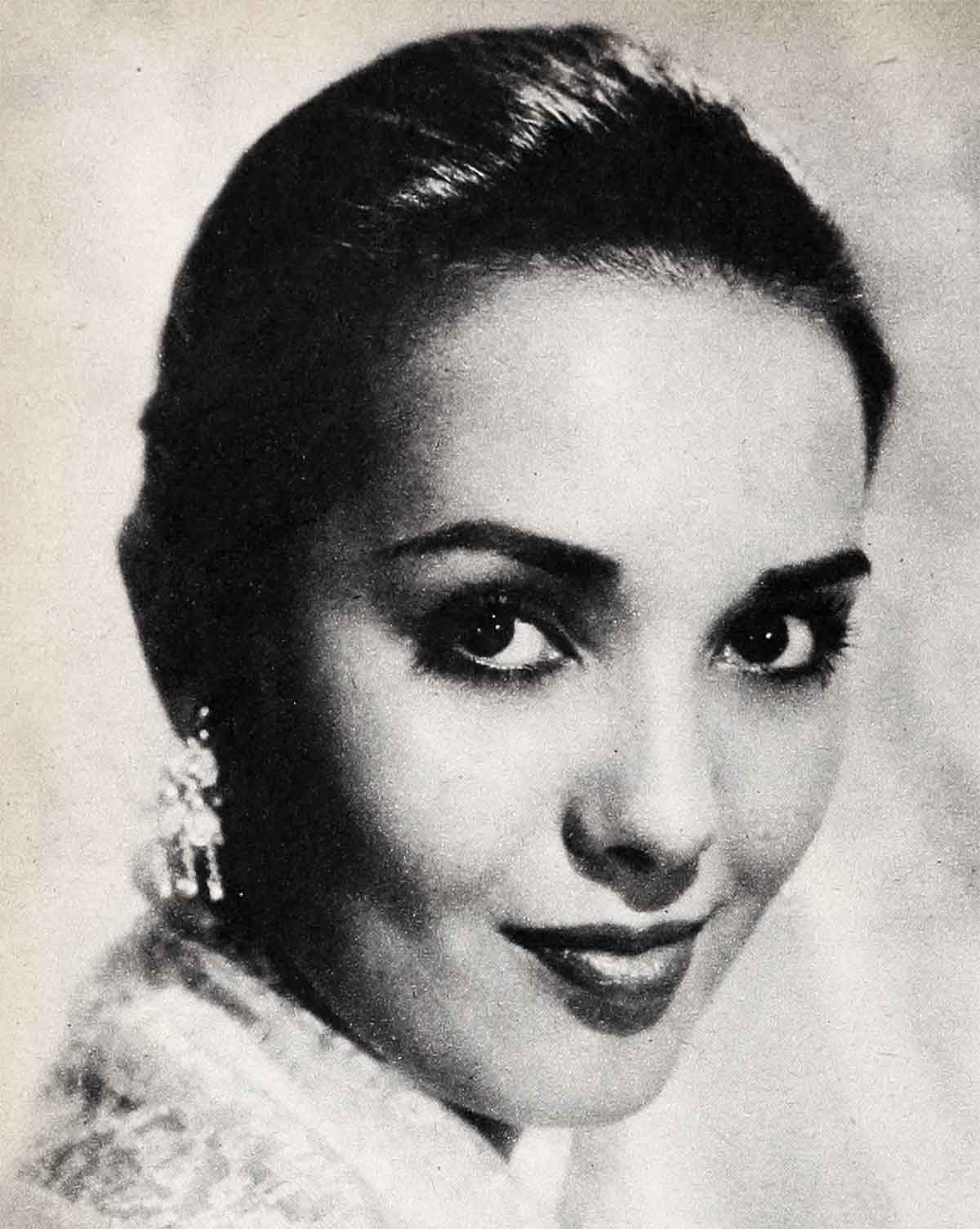

And so when Marlon met, in August, 1956, Anna Kashfi, with her dark, beautiful face, her seemingly Eastern manner of self-contained, quiet solemnity and the gentle manner of Europe, his search for love had turned up a seemingly perfect object. When Marlon returned to Japan to make “Sayonara,” he became more and more sure. He was no longer the restless young talent in films: He was a businessman with his own Pennebaker Production Company; and in his life there was no more room for the restless young lover. He wanted a home and children. In October, 1957, Marlon Brando married Anna Kashfi at a quiet ceremony at the home of his aunt.

When the newspapers broke with stories purportedly refuting the fact the she was Indian, Marlon remained silent. “I love her,” he told those members of the press towards whom he had once been so silent. It was as if to say he did not care whether she were Indian or Welsh, that he had married a woman, and not a national origin. Marlon had made his decision, and he had, at last, taken himself a wife. And Josianne, with warmth and charming manners, smiled and said: “They will be welcome in my house anytime.”

Then, he went to New York to publicize “Sayonara,” and at night he frequented the Baq Room, surrounded by those same people he had been with that summer of indecision, beating the bongos while those same friends sit by him. The search presumably was over. And yet, how strange that he is there alone. Perhaps, in a larger sense, just as it has since his boyhood, Marlon Brando’s search for love will never end.

In Hollywood the lovely Anna, who was to bear his child, already sensed it. Sensed that in Marlon’s search for love, she had not been the answer. For he had left, to go alone on what should have been a honeymoon—and did not come back. Heartsick, she waited. Would he ever return? Or was Marlon Brando’s love story moving toward an unhappy ending?

THE END

—BY OSCAR ERICSON

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1958

zoritoler imol

23 Nisan 2023It’s actually a cool and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.