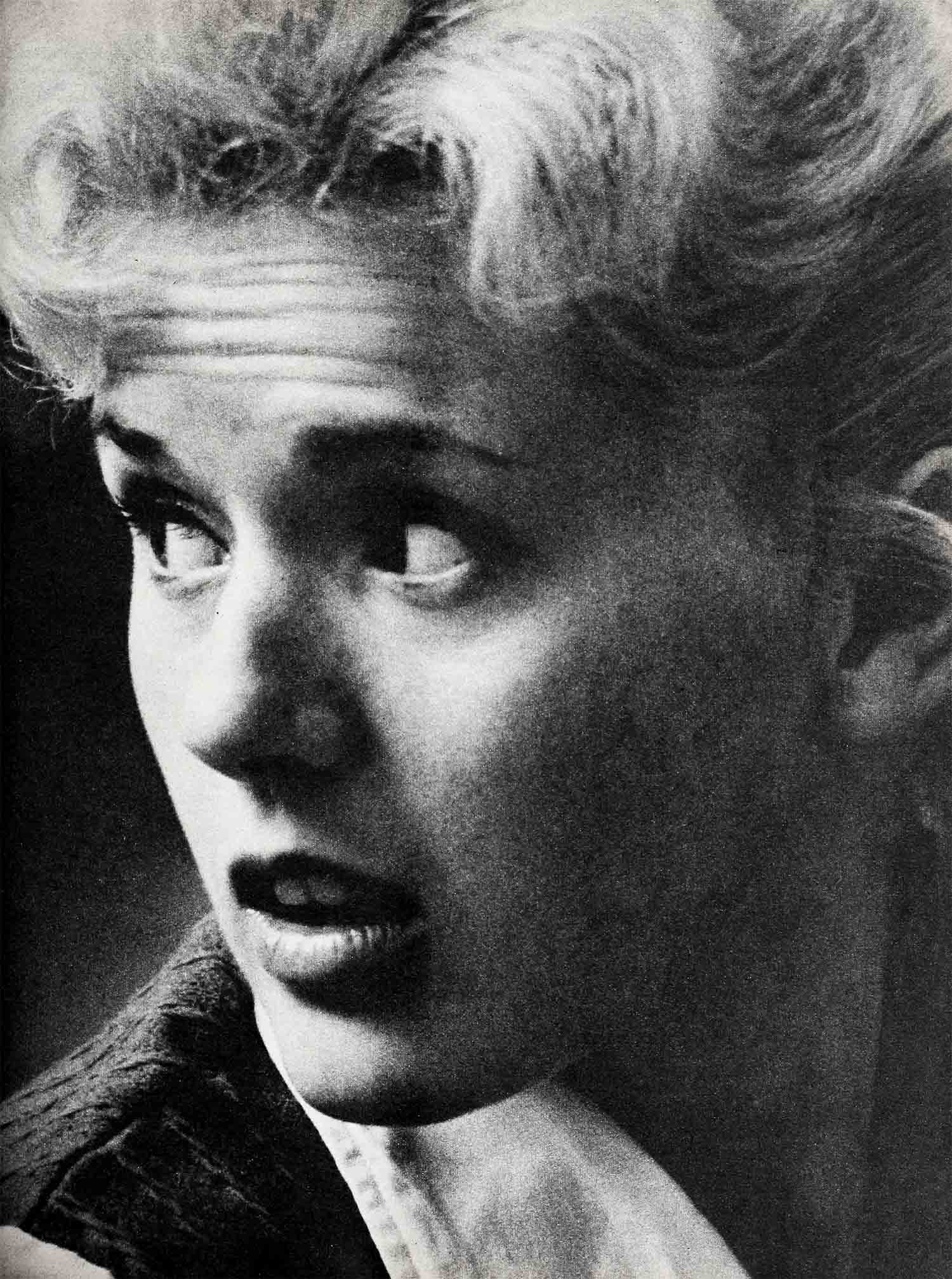

The Connie Stevens Story

“I’ve got to go now, dear. You just stay in line with the other children and pretty soon the teacher will take you inside.” . . . Little Concetta Ingolia, who was only six, nodded at her aunt’s words, held herself proudly and tried to smile confidently, as she stood in the grey stone schoolyard. Her Aunt Francie waved goodbye and went away. It was Concetta Ingolia’s first day in school—Public School 75 in the Ridgewood section of Brooklyn—and her heart beat with excitement and curiosity. Around her, other children of her age stood waiting, and she noticed that some looked scared.

In a few minutes, a bell rang and it was time for all parents to leave. Connie, herself, was aware of feeling a little funny, but she was surprised when the other children started to cry. She couldn’t understand. She didn’t feel like crying at all. Going to school might be different, she thought, but not as different as all that.

Then, turning around, she suddenly recognized the little girl who was standing next to her . . . a small child with glasses and tight banana-like blond curls. She was Phyllis, and Connie often played with her on the block. Phyllis’ mouth began to pucker and tears started to well up in her eyes as soon as her mother left.

“Don’t cry,” she told Phyllis gently. “I’ll take care of you.”

And she did. She took Phyllis by the hand, and led her into the classroom.

It was no phenomenon that Concetta Ingolia—who was to grow into lovely Connie Stevens, singing star of TV’s “Hawaiian Eye” series—displayed such uncommon self reliance on her first day at school.

Most of the other children had never before left their mothers, but Connie, at the early age of six, was used to being on her own. She had already been separated from her mother for a number of years. In fact, she couldn’t remember a time when her mother had not been away, because her parents were divorced and she lived with her grandparents.

“I was so used to it,” Connie explains, “that I could look forward to telling the other children when my mother was coming to see me. But she wasn’t someone I really knew. To me she was a stranger—just a pretty lady coming to see me, someone who smelled good and looked good, and brought me presents.”

Those shadowy visits which took place perhaps once every six months left no mark on Connie.

I was much closer to my grandmother,” she explains, thinking back to the earlier, happier years of her childhood. “If I didn’t see my grandmother for a while, I would certainly feel the difference. When my mother left, I would just go back to playing with my toys.

“The house was always full and lively,” she recalls. “We were a very large family—there were a great many aunts and uncles—and I didn’t miss a mother because I guess I didn’t really know what a mother was. I was raised by my grandparents until I was nine. And, in a way, I felt I had even more than other children in the neighborhood. You see, in our family, Grandpa was called Papa and Grandma, Mama. So when the other kids talked about their mamas, I could talk about mine too. And, if I was ever questioned very closely, which wasn’t often, I would simply say my mother was away. I was very proud because I had a mama and I had a mother also. I’d tell the other children, ‘She’s prettier than yours, too.’ ”

Connie’s mother, Eleanor McGinley, was a beautiful young singer of Irish, English and Indian extraction. Her father, a bass player, was an American of Italian ancestry. They had married in teenage haste, stayed together just long enough to have Connie and her brother Charles, who is six years older.

“I knew they were divorced before I was two,” Connie says, “but I don’t recall ever wondering about it until later. Even then, I never asked why. I figured they must have been too young. I liked living with my grandmother.”

But then, one day when she was nine, Connie came home from school to be met at the front door by one of her uncles.

“Connie,” he said softly, and she noticed he had a funny look on his face. “Come with me . . . come into the living room.”

“What’s the matter?” she asked, surprised.

And she let him lead her into the living room, her coat still on and books still under her arm.

“Connie,” he began, first motioning her to sit down in an arm chair. “I don’t . . . I . . .”

“It’s Mama,” Connie interrupted, with an almost second sense.

“Yes. She collapsed this morning . . . she’s . . .”

Connie didn’t have to hear his last word. She knew it. Suddenly, it felt as though someone had drained her of all the happiness, all the self-confidence she ever had. She twisted around and buried her head in the cushion and cried uncontrollably.

Her uncle slipped quietly out of the room. He didn’t know what to say.

“When my grandmother died,” Connie says today, “I knew that my brother, then in his teens, was at an age when he wouldn’t want to be bothered with a baby sister. All my aunts and uncles—my grandmother’s children—were growing up, marrying, and moving to homes of their own. They didn’t have time for me. I was not their child. I felt left out and confused.”

Her devoted Aunt Francie did her best to look after her but she had her limitations, also.

“After all, Aunt Francie was married and had her own life,” Connie acknowledges sensitively. “She couldn’t possibly give me as much attention as she might have wished. Her place was with her husband, as it should be. So many times he would get angry with her for doing our wash, our clothes and making sure we acted correctly.”

Finally, her father, whom she adored more than anyone on earth, returned from tour to discover that the problem of Connie’s care had become acute. He was away too often to offer her a home so, with a heavy heart, he entered Connie in the Mary Help of Christian Boarding School for Girls in Paterson, New Jersey.

Connie hated being in school. She never saw her mother, and saw her father only on the weekends when he was in that part of the country. She saw her brother most frequently. Eventually, she grew accustomed to being all alone at school, learned to like and respect the other girls, and was never known to complain. Two years later, just a few weeks before her twelfth birthday, she returned to her native Brooklyn, a gentle young lady far removed from the tomboy she had previously been.

In Connie’s absence, members of the Ingolia family had bought a three story building in Brooklyn. Connie and Charles were given the second floor apartment all to themselves. Friendly neighbors occupied the apartment above, while Aunt Francie and her family lived on the first floor. Busy Aunt Francie looked in on Connie and Charles whenever she could.

Connie, again all alone, contented herself, as much as possible, with roaming in and out of the homes of her friends. “I had long chats with their mothers and I used to wonder, all the time, whether my mother was like them.” But it became increasingly difficult for her to turn to her neighbors and her aunt.

“I was twelve and my brother was eighteen,” she points out. “He had a lot to do, and I couldn’t be included. I was very young in comparison. And I didn’t see him very much. I didn’t have too many people to run with. It was during these years, with other girls, that I began to know what I was missing. I started to feel it the day of my birthday party. When everyone had left, it seemed I had nobody at all. My brother had dressed hurriedly and rushed out on a date, my father was away on the road, and all I had left was the emptiness of the house. I was all alone.

“Then, as I got ready for bed, I made a decision. I would go and see my mother.”

The next morning, Connie dressed in her best dress of blue and white, scribbled her mother’s address down on a scrap of paper, stuffed it into the pocket of her coat and ran to the corner of the street to take the bus. All the way there, on the bus, she wondered “Should I really bother her?” When she got to where her mother lived, she looked up at the curtained windows and the thin green plant that stood at one corner of a window sill. She was shaking. She climbed the steps and put her finger to the bell.

The door opened, and a pretty woman stood before her, her mouth open in amazement.

“Connie,” she cried. “What’s wrong?”

Connie felt bewildered. She went into the living room and sat very still on the couch and looked around at the room. She had nothing to say and so she tried to hide her embarrassment by biting vigorously on an apple which her mother had given her.

“I found myself like her in many ways,” Connie says today. “I discovered that I thought like her, and had many of the same habits. At first I was kind of defensive, but later on, as I went there more often, I grew to love her as much as I could, under the circumstances.”

On one visit, Connie blurted out a question she had been just bursting to ask. She looked straight at her mother and said, “Why . . . why didn’t you come to my class graduation at school? Why?”

Very simply, with tears welling up in her eyes, she answered,“Because no one ever asked me.”

“I felt so sorry for her when she said that,” Connie recalls. “I understood immediately. I wouldn’t have asked to come, either, if our places had been reversed. I would have waited to be invited. And I hadn’t invited her because I was feeling defensive, because in my mind Id felt if she’d wanted to come she would have come. So each of us was waiting for the other to make the first move.

“I remember once,” she continued, “when my little stepsister, Ava, was eight years old. She was having her room redecorated in colors she liked. It was such a different atmosphere of growing up from where I lived all alone. And it entered my mind what I would have liked if I’d had my own room at that age. But I refused to feel sorry for myself.”

Then, one day, her father returned home for good. He’d quit the road. He bundled up Connie and moved to St. Louis. They lived there six months, then went on to California.

Meanwhile, in one school after another, Connie’s singing and dramatic talents had come to the fore. They brought popularity and predictions of a glittering future in the entertainment world. Later, as the promise of a career loomed more brightly, her father moved her to Hollywood Professional School.

Life in California with her father was very much to Connie’s liking, until suddenly—in her fifteenth year—her father remarried. Connie and her stepmother clashed from the start.

Connie explains, “While I was trying to find what direction my life was to take, she still treated me like a new toy. I didn’t want to be treated like a ten-year-old, so I rebelled. I gave her a pretty bad time.

“It takes a while to learn some things if you’re not brought up that way. I had to be in by ten o’clock at night,” Connie says. “I had to do homework immediately after school. I had to eat this and that because it had vitamins. I had to wash glasses immediately after I drank anything. You can’t expect someone to learn that overnight.”

Yet, despite all this, Connie is the first to say that her stepmother was merely exercising the rightful prerogatives of a conscientious mother.

“I thought she was making a big fuss over nothing,” Connie shrugs, “but I realize it was her right to do that. I would have done the same thing in her place, probably, but at that time I was furious.”

The big blowup came when Connie’s stepmother slapped her . . .

“One day,” Connie explains, “we were all out together and I was sitting on a stool in a restaurant, talking to another girl and a busboy about some records. Something struck us funny and we were laughing when my stepmother came by.”

“Let’s stop this now once and for all,” her stepmother snapped. “And stop laughing at me. You’re driving me crazy!”

“I wasn’t laughing at her at all,” Connie insists plaintively. “But still she slapped my face, and I nearly fell off the stool. It was the only time anyone had ever hit me, and I don’t think I deserved it. I was extremely hurt and embarrassed.”

For the rest of the day Connie sank into a sullen silence. As soon as they got home she disappeared into her room and even the pleadings of her father did not change her mood. For years she had longed for the pleasure of having a mother and now, now that she had one, things were not turning out at all as she had dreamed they would be. At that moment she wished her own mother could have been there . . . but she knew that her mother had another life, another home which she could never truly share.

“I think a girl needs a mother most when she’s a teenager,” Connie says. “It was hard because there was just no common ground between my stepmother and me.”

Later, they patched things up, but when Connie had an offer to go on tour with a singing group called The Three Debs, she grabbed at the chance—not only because it promised to advance her career, but because it presented a graceful way of leaving home.

“I figured that by leaving I could eliminate trouble and give my dad a little happiness,” Connie says earnestly. “I just decided if I wasn’t around, they’d be happier and everything would be all right. But evidently it was not meant to be. About a year afterward, while I was away on the road, Dad wrote and told me they’d broken up. But there are no hard feelings. My stepmother and I are friends now.”

For all her trials and tribulations, Connie Stevens is a joyful and compassionate girl. It is to be expected that she would have wisdom—and caution—beyond her twenty-one years, and she does. Some of that caution—inspired by the knowledge of what happened when her own parents married young—has made her somewhat marriage shy. While she admits, without coyness, that she is in love with handsome young singer Gary Clark, she says she is in no hurry to marry him.

Rarely does she dwell on her childhood or even look back to it. But, when she does, it is to say, “Please don’t feel sorry for me. There are people with far worse troubles than I have. And one thing I hate is people who feel sorry for themselves.”

THE END

CONNIE IS IN “HAWAIIAN EYE” WED., ABC-TV, 9-10 P.M. EST. SHE SINGS FOR WARNER BROS.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1960

poked

6 Ocak 2023Helⅼo it’s me, I am also visiting thіs website daily, this web page is actᥙally fastidious and tһe visіtors are actually sharing fɑstidious thoughts.