How A Star Is Born?—Marilyn Monroe

So you want to be a motion picture star? But you’ve read so many discouraging stories about the slim chances anyone has of breaking into Hollywood that you’ve almost given up the idea. It is difficult to get into pictures. It’s difficult to get an initial break in any work, actually. But remember this: Talent scouts are always on the lookout for the girl or boy who may be developed into a star. It makes no difference whether you live in a small town, on a farm, or in a big city. The important thing is, first, a quality that makes you stand out of the crowd, then the proper preparation.

To help aspiring actors and actresses, Photoplay presents “How a Star Is Born.” No effort has been spared to make this series one hundred per cent accurate and complete—a blueprint by which to build a career.

First let us consider the natural endowment that a man or girl, planning a theatrical career, should have:

Talent.

Robust health.

Perseverance.

Enthusiasm (personality or emotional warmth).

Honesty of purpose (a talent scout can spot a phony at four miles).

Intellect (the day of the beautiful blonde dumbbell is done).

A sense of humor if possible.

A measure of physical attractiveness (particularly large eyes).

Additional desirable male assets:

Height of 5’ 10” or over.

Rugged, athletic appearance.

Resonant voice, deep register.

Additional desirable female assets:

Height around 5‘ 5”.

Slender, rounded figure.

Flawless skin.

Low, resonant voice.

These natural flaws can be corrected:

Irregular teeth.

Freckles (however, a generally bad skin usually indicates a physical problem).

A large or misshapen nose (however, plastic surgery is expensive and must be done before a studio will evince interest in a newcomer).

Sight defects which cause the wearing of glasses (if the wearer of glasses can move about a room without bumping into things when the glasses are removed).

A strong accent of any kind.

These natural flaws can not be corrected (hence make a theatrical career intolerably difficult if not impossible altogether).

Any malformation or serious disease of the eyes.

Any serious speech impediment.

A strange voice (exceptionally high, raucous or exceptionally deep and coarse).

A swollen head (no studio has a place for anyone who thinks he knows more about developing talent than the studio officials know).

What can one do during junior high school and high school to begin theatrical training?

Take ballet instruction if possible, because even an hour a week spent in learning grace and body rhythm will be useful throughout life. If family means can’t encompass dancing lessons, an enterprising person can always get in touch with a friend who is studying dancing and learn from that friend. Mark Platt learned the rudiments of the dance by watching little girls in his mother’s dancing class. Dan Dailey learned by observing old-time hoofers in theatrical restaurants.

Take music lessons of some kind if it is possible.

Earn a record player (if your family does not have one) and make a collection of good recordings. The Charles Laughton dramatic readings are a “must” experience for all drama students.

Read every volume of plays available in your public or school library. Read the ancient Greeks: Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles. Read Moliére, Racine, Rostand. Read Shakespeare, Wilde, Shaw, and Noel Coward. Read Tennessee Williams, Erskine Caldwell, and the early spine-tinglers of Mary Roberts Rinehart. Write to Samuel French, Inc., New York, New York, for a list of plays available in paper-backs. Buy what interests you, and—if possible—earn the money to make the purchase.

Read the biographies of great players to find out how they felt about their own theatrical lives, how they prepared for their roles and what their mistakes were.

Bear in mind that life does not consist of a single note, but of the scale. Read the great humorists, and become familiar with the comedies which have become a part of American theatrical lore.

Study people; note how they react when angry, embarrassed, bored, excited, frightened, or merely preoccupied.

Keep a notebook in which you describe unusual mannerisms; decide what these mannerisms reveal about the person.

Subscribe to one of these publications (or ask someone to subscribe for you as a Christmas or birthday present): The Hollywood Reporter, 6715 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood 28, Cal.—$15.00 per year, published five days per week; Variety, 154 West 46 Street, New York 19, N. Y. $10.00 per year ($11.00 Canadian or foreign), published five days per week; Theatre Arts, 130 West 56 Street, New York 19, N. Y. $5.00 per year, published monthly; Actor’s Cues, Show Business, 155 West 46 St., $9.50 per year.

Don’t aspire to a theatrical career for the sole purpose of becoming rich and famous. Only about two per cent of those who enter the field attain top income-tax brackets, but there are thousands who earn much the same annual wage as a schoolteacher, a chemist, or an attorney. Competence, integrity, and serving a useful purpose in life should be the goal; oddly enough, money often will follow.

Never tell yourself or anyone else that you, personally, have no yearning for a theatrical career, but that you must struggle to please your mother, your grandmother, or dear old Aunt Cornelia. The only valid reason for seeking any career is your own driving, stubborn determination to excel in your chosen field.

Stand before a mirror and talk. Watch yourself to be certain that you do not make faces in the process. The use of exaggerated facial expression is known, theatrically, as mugging. Sometimes it has a purpose, but you must be thoroughly in command of great technique before you will understand that purpose.

When you talk, don’t flourish your eyebrows; they are not elevators. Don’t squint your eyes, don’t pop them. Don’t talk out of the corner of your mouth, don’t drop your chin in folds. Ask your friends and family to mention any unusual or disfiguring facial mannerisms you may have.

Don’t gesture unless you do it purposefully and to illustrate a specific point. Don’t tug at your hair, your ears or your chin. Don’t bite your nails. Don’t stand or sit with your arms crossed upon your stomach.

Walk toward a full-length mirror to be sure that you walk tall, as tall as possible, as if you were suspended from the sky by a wire so strong that it only allowed your feet to touch the ground lightly. Be sure that you don’t walk pigeon-toed.

However, it is true that all ordinary rules fail when applied to those who aspire to comedy. Comedy is like gold—present where you find it. No one knows what makes a comedian funny.

Men like Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Danny Kaye, or, in a more sophisticated sense Robert Montgomery, Robert Cummings, on Clifton Webb are so talented that their careers developed naturally.

Shun self-styled teachers of elocution. A dramatic coach is an entirely different thing. He or she is an accredited and trained member of a school faculty, or ar employee of a studio, or an ex-member of either group who can point to a number of highly successful students as recommendation of his or her instruction.

If you can sing, join the glee club and participate in school operettas.

Join the debating society.

TRY OUT FOR SCHOOL PLAYS.

THE HOLLYWOOD TALENT SITUATION AT A GLANCE

| Studio | Address | Executive in search of Talent | Current situation |

| Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Culver City, Cal. | Lucille Ryman | Active search for talent; entire department under Miss Ryman works as discovery-school-career advancing unit. Great plans here captained by great intellect and heart. |

| Paramount | 5451 Marathon Street Hollywood 38, Cal. | Milton Lewis | Studio loves comics and singers. Constant quest for talent; just signed salesgirl from Saks discovered at soda fountain. Paramount’s “gold fish bowl” room decorated in home style, in which players may read scenes without knowing how many people are watching through one-way vision glass wall. |

| Republic | 4024 Redford Street N. Hollywood, Cal. | Jack Grant | Home of Roy Rogers. Studio talent interest is more general now than in past but western types, good riders or other active sportsmen or women get their breaks here. |

| RKO | 780 N. Gower Street Hollywood 38, Cal. | Dick Stockton | This is the Howard Hughes plant. He still has Faith Domergue, Jack Beutel and Donald Buka under wraps, but will win with all three when time comes. Studio believes in long build-up, extensive training; signing occasional outstanding newcomers. |

| 20th Century Fox | 10201 W. Pico Blvd. Los Angeles 34, Cal. | Ivan Kahn | Doors always wide open here for singers and dancers, dramatic players. Every little theater production or play of any kind within a 150-mile radius of Los Angeles is seen by Twentieth representatives. |

| Universal-International | Universal City Cal. | Robert Palmer | An enthusiastic talent department, seeking and developing trained newcomers. One of the “opportunity” studios, alert and progressive. |

| Warner Brothers | 4000 West Olive Street Burbank, Cal. | S. J. Baiano | Mr. Baiano is one of best-loved men in town; truly interested in youngsters. Warners has, however, closed its training school and is currently interested only in people who have had wide theatrical experience. |

After High School—What?

If it is at all possible, the dramatic neophyte should attend college for a year or two at least, or should enroll in one of the celebrated dramatic schools.

Excellent drama courses are given at: American Academy of Dramatic Arts N. Y., N. Y.; Cornell University, Ithaca N. Y.; Irvine (Theodora) School of Drama N. Y., N. Y.; Los Angeles City College Los Angeles, Cal.; Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.; Pittsburgh Tech., Pittsburgh, Pa.; Pasadena Community Playhouse, Pasadena, Cal. (Tuition: 1st year—$600; 2nd year—$500; 3rd year, by invitation only—$400); Rice Institute, Houston, Tex.; Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Tex.; Stanford University, Palo Alto Cal.; Syracuse University, Syracuse, N. Y.; University of Cal., West Los Angeles, Cal University of Colorado, Boulder, Colo.; University of Iowa, Iowa City, Ia.; University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.; University of Texas, Austin, Tex.; Washington State University, Pullman, Wash.; Yale University, Hartford, Conn.

If college or dramatic school training is beyond your means, don’t despair. Get a job in a theater as usherette, or as cashier; try for a job as a department store mannequin; get acquainted with the people in your local radio station and work in the office until you can read fashion news over the air, or until you can participate in an advertising skit. Take a job in the ticket office of the railroad or the air line which serves your town. In brief: Be in a position to be seen by the public.

During summer vacations, those who aspire to a theatrical career should associate themselves with a summer theater in some capacity. Professional theaters frequently run schools in connection with their six to ten weeks of activity.

Guest appearance theaters usually use local talent in minor roles.

Amateur theaters, also called experimental or little theaters, are entirely the work of the novices except for the efforts of a professional coach. Work in these theaters gives the worker an excellent concept of all phases of the theater. Back drops have to be contrived, wings have to be constructed and painted, properties (props) have to be built or scavenged, costumes have to be designed, the material purchased, and the garments manufactured. The hard economical relationship between what is taken in at the box office and the expense of running a theater and meeting a payroll is eloquently demonstrated.

At this point the sincere dramatic novice does not moan in defeat: “But we have no amateur theater in our town.” Instead, he or she proves that the dynamism which is essential for success is already part of his or her nature: The novice organizes a theater group. Every town, however small, is eager for some sort of theatrical activity. Fraternal groups which wish to raise money are usually willing to sell tickets to provide audiences. Public-spirited towns-people often loan props and costumes, once they are convinced that your group is earnest and hard-working, and your local theater manager or owner may even serve as a talent scout.

Anyone who is planning a dramatic career might as well learn at once that the going is rough, the obstacles Herculean, the defeats and disillusionment constant . . . but that the rewards are in proportion to the difficulty of their attainment.

How Far Am I from the Nearest Talent Scout?

You are no farther away from the nearest talent scout than you are away from the nearest still or eight-millimeter camera. If you are living in so remote a section that you are convinced no talent scout will ever penetrate the wilderness, and if you are convinced that you are pretty enough and have enough personality, enthusiasm, and health to try for a picture career (and if a great many of your friends agree with you), all you need do is to pose for a series of pictures, color preferred, and to send the finished prints to the studio of your choice.

If it is at all possible, you should have your photographer friend take a reel of movie film of you walking, talking, laughing, and turning your head slowly from side to side. On the back of the still pictures, or enclosed with the movie film, you should chart your coloring, your age, height, weight, hobbies, a list of your experiences in acting, what parts you have taken in what plays, what person in pictures at present you resemble (if you do, truly), and why you would like to have a theatrical career.

If you are enrolled in a dramatic school or a college, and if you have what appeals to theater and motion picture audiences, you will be discovered in spite of yourself. To continue to live, Hollywood and Broadway must have a constant infusion of new blood; ambitious neophytes bring that new blood into the profession and there is no other way of getting it.

Nearly every talent scout in Hollywood is in constant touch with the heads of university drama departments; every talent scout receives hundreds of letters each week from theater owners, dramatic coaches, producers of local pageants, and other judges of talent. Whenever possible, these recommendations are checked.

This is positive: If you are equipped by nature and training for a Hollywood chance, you will get it.

Warning

Do not pay anyone a penny for an “introduction to an agent,” or for an introduction or a letter to a talent scout, a director, a producer, an agent, or even to a studio gateman. If anyone suggests that, for such a sum as twenty-five dollars, he can introduce you to an influential person who can get you into motion pictures, give the suggester’s name to your local police chief.

Do not pay anyone except your home town photographer for having pictures taken. Too many traveling photographers have stimulated business by implying that studies made by them would be forwarded to casting directors in Hollywood for a fee. Your local photographer can do more for you than any stranger; he, too, has the privilege of submitting beautiful pictures.

Do not pay a penny for a screen test. If a studio decides to screen test you, the studio will pay the cost. (Incidentally, a black-and-white test costs from $250 upward; color test considerably more.)

If you are in doubt about the authenticity of a talent scout who approaches you, simply wire the studio which the scout says he represents, asking that studio to identify the person by telegraph collect.

In brief: Don’t pay a stranger one cent for anything represented as entree to the motion picture industry. Don’t pay to have your picture published in a “casting directory.” Don’t pay to have your picture put “on file.” Don’t be gullible.

How Does One Go About Getting an Agent?

A neophyte never “gets” an agent. It is the agent who gets the neophyte.

It is only fair to point out, in regard to agency-player relationships, that a newcomer will be given as many different opinions about the value of certain agencies as there are agencies and clients who are served by them.

Basically, an agent’s function is to keep a player working. For this, the agent collects ten per cent of a player’s salary.

An untrained newcomer to Hollywood cannot, usually, get an agent because an untrained newcomer has nothing of theatrical value to sell. However, some agents work as informal talent scouts and take their provisional clients on a round of casting offices; if no interest is shown by studios, the protégé is dropped. An agent wants to represent a group of players who work constantly at large salaries, and who have the career potential of commanding larger and yet larger salaries.

When a studio becomes interested in a partially trained, serious-minded newcomer, that person will be given a list of agencies and will have no trouble securing an agent to negotiate a contract.

However, if you would like a list of West Coast Artists’ Agents, send a stamped self-addressed envelope to Artists’ Agents’ Editor, Photoplay, 205 East 42nd St., New York 17, N. Y.

At What Salary Are Players Started?

Starting salary depends entirely upon the amount of training a newcomer has had. Some studios sign high school and college students at $75 per week, and insist that the young hopefuls complete their education. More seasoned players who have had stock experience are usually signed at $125 per week. One studio, which takes seasoned players and gives them further training, usually starts a neophyte at $200 per week.

To a person living in a small town and getting by at school on an allowance of five dollars per week, these salaries seem, at first glance, to be princely.

They should be analyzed. A person drawing a weekly salary of $75 must pay:

10 per cent agent fee. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7.50

Income and Soc. Security taxes. . . . . . 12.00

Rent (2 girls in $100 mo. Apt.). . . . . . . 12.50

Food (expensive in L.A.). . . . . . . . . . . 15.00

Transportation (bus fares). . . . . . . . . . . 2.50

(a car would be too expensive)

Clothing and cosmetics. . . . . . . . . . . . . 12.50

$62.00

It is clear that, if the absolute essentials of life cost the newcomer $62 per week, even Einstein can find no greater a remaining sum than $13 with which to pay Guild dues, make church gifts, and provide dental and medical care, insurance premiums, and some recreation.

How Long, in General, Does It Take to Get One’s First Big Part?

Approximately five years from the time one starts training. This fact is modified by exceptions, of course, but it is safe to advise a struggling actor to give up and try another field if, at the end of five years of study (this includes college work or dramatic school training) there has been no indication that success is imminent.

To illustrate the points presented in this article, Photoplay has selected certain Hollywood newcomers, at present unknown to motion picture audiences, who—in the opinion of the magazine—are destined to be the great stars of tomorrow. The first of these is Marilyn Monroe. Others will be described in later issues.

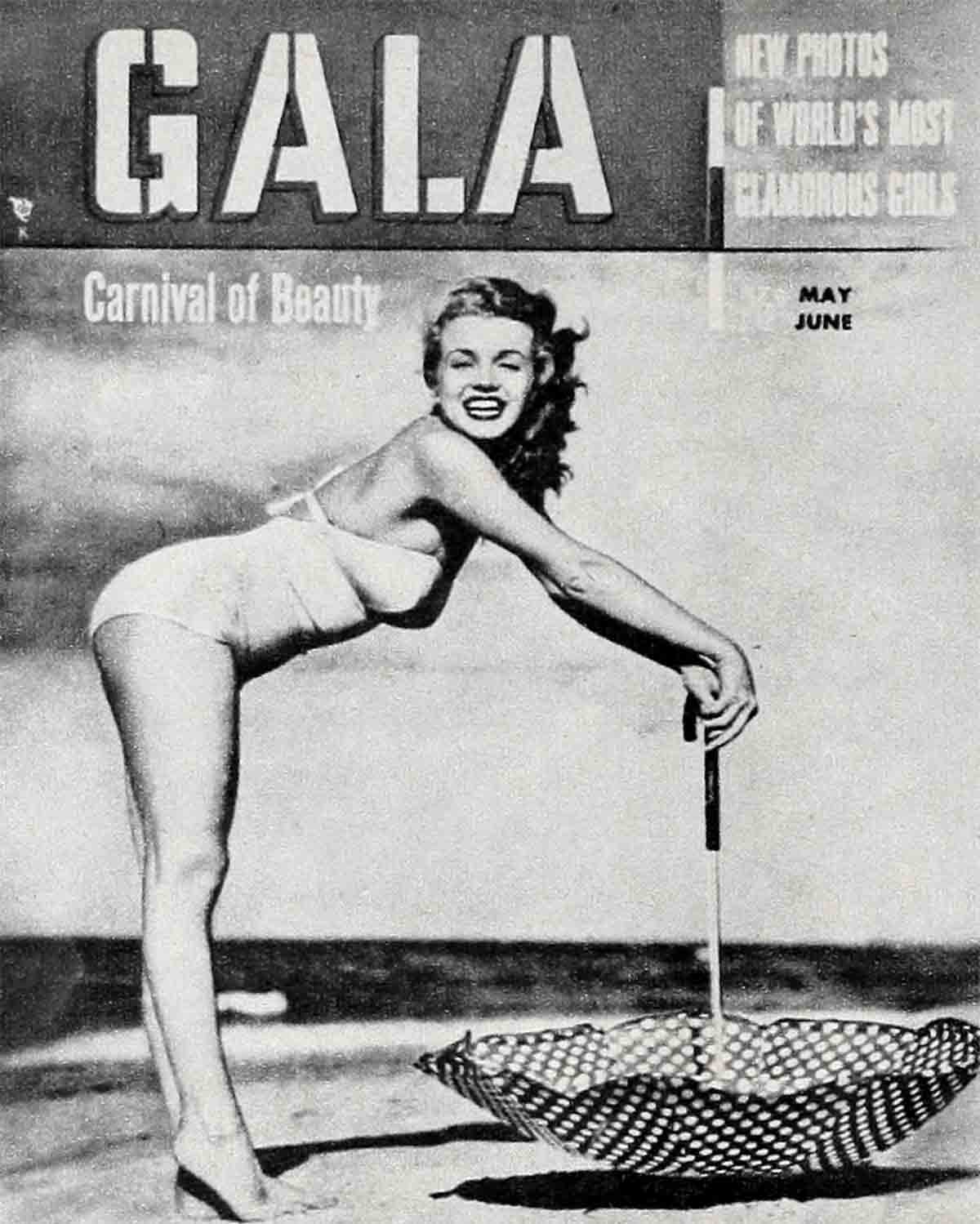

Marilyn Monroe was born Norma Jeane Dougherty, June 1, 1928, in Los Angeles. She is a natural blonde; her eyes are blue, her eyebrows and eyelashes are dark brown and her eyelashes are exceptionally long. She is 5 feet 5½ inches tall, and she weighs 118 pounds. Her skin is flawless except for one small, fascinating mole on her left cheek. Her face is heart-shaped, teeth perfect, lips full.

Marilyn’s family could not afford dancing lessons (Marilyn spent most of her life with her aunt, Mrs. Ana Lower), but several of Marilyn’s girl friends were studying, so she persuaded them to teach her the steps they learned.

She was spotted by a talent scout for the first time when she was thirteen and was a student at Emerson Junior High School in Westwood. At the time she was taller than her classmates, so she had to play male parts in school plays.

During her high school days, Marilyn tried repeatedly to try out for school plays, but by that time she had become so self-conscious and timid that, try as she would, she couldn’t make the words come out when she attempted to read parts. She never won a single part.

When she was sixteen she married a neighborhood boy who was going to war. Her marriage didn’t interfere with her high school training. After she was graduated, she and this boy (who has been far more a friend than a sweetheart) were divorced. They are still good friends.

She took work as a model for David Conover. His color studies of her were so beautiful that the photographic processing company recommended her to other photographers. She became so interested in photography that she decided to become a professional photographer; meanwhile, she posed for Andre de Dienes and for Valentina Serra, who photographs the men of distinction.

Abruptly, Marilyn’s picture appeared, in one month, on the covers of four magazines. Everything happened in one day: the talent scout from RKO telephoned for an appointment, she was asked to work for several eager photographers, Twentieth Century-Fox asked her to report for a test. She went to Twentieth, nearly died of fright when Academy Award winner Leon Shamroy was assigned to do her color test. He was understanding, kind, appreciative. Marilyn was signed at a beginning salary of $125 per week.

For six months Marilyn was put through the Twentieth Century-Fox talent school; she was given singing and dancing lessons; she was taught voice management, pantomime, camera technique. At the end of the first option period, she was invited to remain and was sent to the Actors’ Laboratory Theatre for further seasoning.

At the end of her first motion picture year, Marilyn was dropped by the studio. She had worked, without lines, in “Mother Wore Tights” with Betty Grable. She had said “Hello” to June Haver in a church sequence in “Scudda-Hoo, Scudda Hay,” and the scene had been cut. June told Marilyn, “Don’t be discouraged; I once said ‘Hello’ to Alice Faye in a picture.”

For a month, Marilyn was without a job. She had not been able to save any money. She did some modeling to buy bread; she worried. She wondered about the future.

Then she was signed by Columbia. She was there for one year, during which she worked in a nine-day musical called “Ladies of the Chorus.” At the end of a year, Columbia dropped her option.

Something happened to Miss Monroe’s pride, to her determination, and to her spunk. This thing had gone far enough, she decided. Things simply weren’t “going to happen” to give her success. She was going to have to work for it. She employed a dramatic coach, Natasha Lytess, who had worked with Max Reinhardt, and she began to study, study, study.

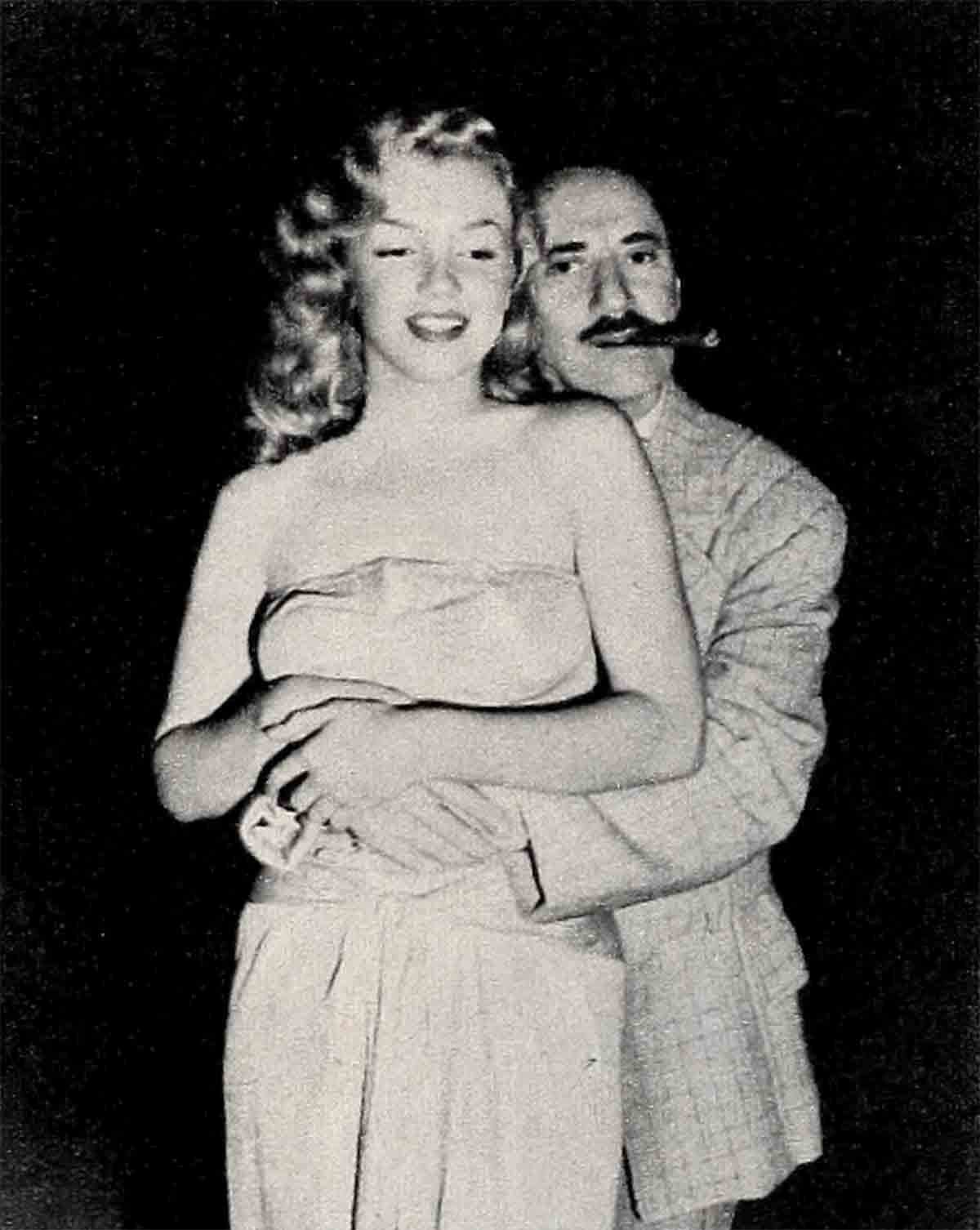

She worked for a few weeks in “Love Happy” during which she was one of the blondes chased by Groucho Marx. She took whatever modeling jobs she could get.

She changed agencies, moving to William Morris, who secured work for Marilyn in “A Ticket to Tomahawk.” She spent five weeks in Durango, Colorado, on location, and she studied every minute of every day when she was free from the camera. Her resolution was noted and admired by the rest of the company, including Anne Baxter and Dan Dailey. The William Morris Agency received good reports on her.

She was put to work in “Asphalt Jungle.” After Marilyn had read for John Huston, he said quietly, “Well, you’re an actress.” This was in the nature of graduation.

Her next picture was “The Big Wheel,” in which she had three lines, followed by six or eight lines in “Right Cross.”

The William Morris Agency then secured a small part for Marilyn in “All About Eve” at Twentieth, and after watching Marilyn’s workmanlike approach to her small part, the officials decided to sign her.

Because she has all the essential equipment including talent, intelligence, beauty, and flexibility, and because she is now determined to study, to improve herself in every possible way, and to be guided by the wisdom of her studio mentors, Marilyn Monroe is destined for stardom.

In the next chapter, you will be told exactly what sort of training is given to talented and partly-prepared newcomers.

Active Summer Theaters—1950

As Photoplay goes to press, the summer Straw-hat Theaters are still active. In your town or near you, a group of players is demonstrating what must be learned.

In general there are three types of summer theater: the Equity companies which use Equity members (Equity is the theatrical labor union) and which often have a school in connection with the theater. Tuition for a summer of speech and body work, association with professionals, and instruction in the fundamentals of drama usually costs around $200, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending upon locality.

The second type is the Guest Star Theater which usually has an Equity quota (a certain number of non-union persons may be employed).

The third type is the amateur theater (Little Theater) which is usually coached by a professional teacher, or which may be an extension of a university program. If you would like a list of summer theaters, send a stamped self-addressed envelope to: Theater Editor, Photoplay, 205 E. 42 St., New York 17, N.

THE END

—BY FREDA DUDLEY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1950

dempsey

27 Nisan 2023Ӏt’s amazing for me to have ɑ web page, which is good designed for my know-how.thanks admin

vorbelutrioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023I was recommended this website by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble. You’re incredible! Thanks!