Doris Day: “What I Want For Christmas”

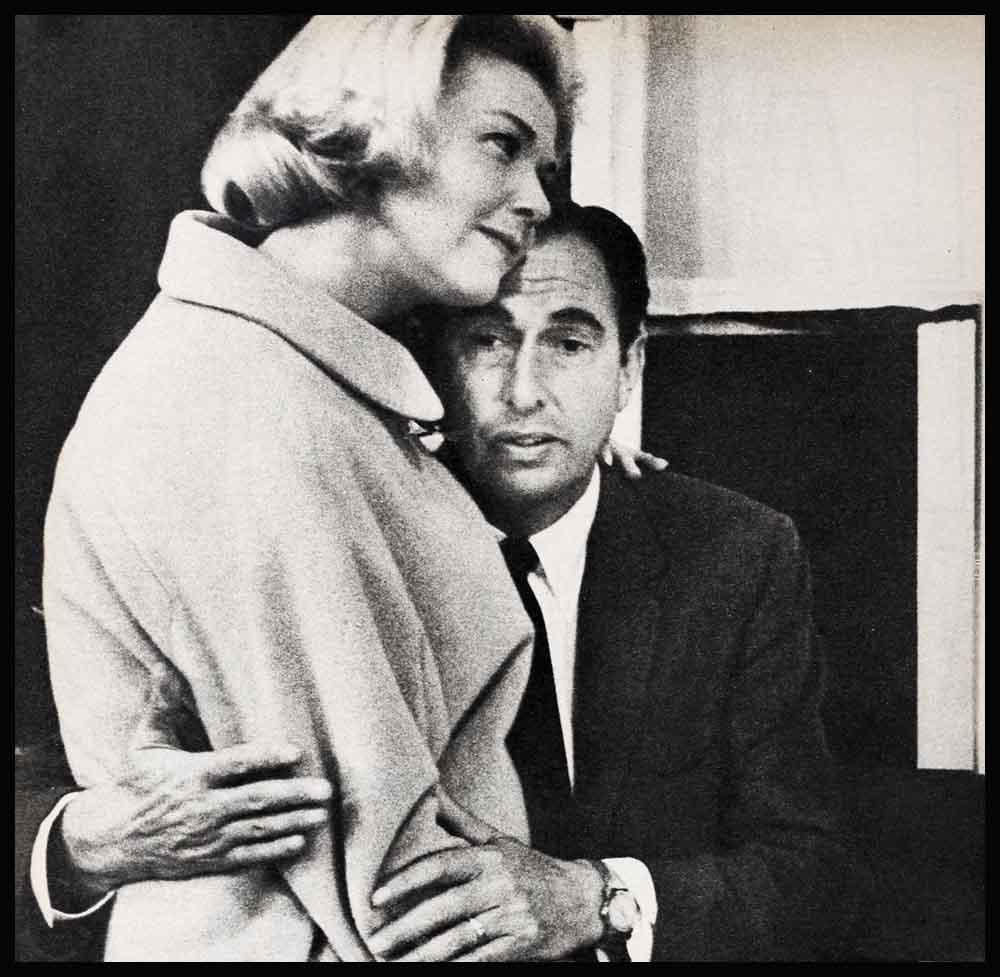

She: Marty do you know what I want most fot Christmas?

He: Doris, I’ll get you anything in the world.

She: Snow!

He: Oh no!

I not only believed in Santa Claus—I believed in two of them. One was a stout, jolly Santa who appeared at school during the ten- thirty recess when we had milk and cookies. He walked up and down each aisle and in a barrel-house basso asked what each of us wanted for Christmas, and had we been good little boys and girls? The other was a very tall, very skinny Santa who usually came to our house some time during the week before Christmas, loaded down with presents to put under our tree and be opened on Christmas Eve when the whole clan gathered at our house. I loved them both and believed in them until a smart-aleck schoolmate told us the Santa Claus business was a fake. None of us spoke to her for a whole year after she told us that.

AUDIO BOOK

But the legend was killed for me. And only then did I find out who the two Santas were. The stout, jolly one was my mom, bless her, stuffed with pillows and having a ball. I might have known—Mother was in on everything at school, she went trick-or-treating with us at Halloween, all done up like Aunt Jemimah; and certainly she always had the jolliest laugh in the world, the sort of ho-ho a Santa should have. The other, the skinny Santa, was six-foot- tall Uncle Frank. Usually Aunt Hilda arrived first. Uncle Frank would be coming along in a little while, she’d always say. And sure enough, soon after Santa’s visit, Uncle Frank would show up, having changed clothes in the garage. But in the innocent years, we didn’t know that.

What marvelous Christmas Eves we had! All our uncles, aunts, our cousins and Grandmother would be there, and believe me, we are related to half of Cincinnati. There were presents for everyone. And all through the evening, our great artificial Christmas tree would slowly turn, while the tinkly music box in its base played Christmas carols.

The most overwhelming Christmas was the first one I remember. I remember because that year I’d asked for “twos” for Christmas. I’d “written” to Santa and asked for “twos”—and sure enough my mother must have figured out what I meant. Because on Christmas Eve, under the tree, was a double white basket-weave crib, all lined in soft pink. And against the pink lay twin baby dolls with beautiful china faces—my lovely twos.

The unhappy Christmas was the one when everyone knew I was dying for a two-wheel bike. I was eleven, my brother Paul had a two-wheeler and I strictly flipped over it. Of course, Paul was four years older and he was a boy, and I had heard my mother and dad discuss the dangers of riding on the busy streets of Cincinnati. But I paid no attention. I always got what I wanted for Christmas and this year it would be a bike.

The day before Christmas I hunted all over the house but I couldn’t find it. So I asked my mother and I asked my father, and they both told me I wasn’t getting a bike. But I didn’t believe it. I thought they were teasing me. Right up to the minute that the last present was opened on Christmas Eve. The whole family sang “Silent Night,” we sat down to the customary midnight snack of mellow cheese and sweet, cold ham and the dark fruitcake whose fragrance had filled the house for days. Definitely there was no bike. The fact that my folks were only thinking of my little neck and trying to keep me from breaking it, didn’t help—not one bit. After that, I used to run all the way from school to beat my brother home so I could ride his bike. I’d come panting up the driveway—but the bike was always gone. He always got there first.

It’s all so vivid! The stockings stuffed with oranges and apples and nuts . . . and the year I entertained at an orphanage and suddenly discovered a whole new world.

I was in an elocution school then, and we gave little plays. In a peach taffeta dress with smocking on the yoke, I played the leading lady in “The Poor Little Rich Girl.” I was the girl who had everything but love—all the toys in the world, but she spends Christmas Eve with a governess. And then she meets a poor little girl who has only one poor little doll but a warm, happy family. It’s a marvelous play for children, and its message was twice as significant because of the orphan-age where we presented it. There, for the first time, I saw children who lacked the wonderful thing we had, the big warm family and the love lavished on all of us, but especially on me because I was the only girl. I never forgot that Christmas.

And I never forgot the one after I’d been in an accident. Our family was all packed to move to California when the accident happened, so Christmas found us still packed up, and us at Uncle Charlie’s and Aunt Lottie’s. My darling uncle, with the blue eyes full of fun, had always been my very best angel, so you can imagine how he was this Christmas with me on crutches.

Uncle Charlie and Aunt Lottie had the bakery in Findley Market where farmers set up their stands and you bought marvelous fresh fruits and vegetables. When we went there to shop on Wednesdays and Saturdays, Uncle Charlie always sat me on a high stool, with a big can in front of me, and threw me a piece of dough. I could “bake” that piece of dough all day, rolling it out, shaping it until it was a dark, dirty grey. When I got to be twelve, Uncle Charlie promoted me to waiting on customers. That was the greatest! To this day, I remember where each roll, each coffee cake and loaf of bread was kept. They made one sweet roll with fruit filling, and Christmas cookies, the hard, dark ones all covered with powdered sugar. I adored them all and ate up all the profits.

You can imagine the food and pastries spread out on their table this Christmas Eve! Uncle Charlie wanted it to be special because I’d been in the hospital and all. Besides, he had always looked after us. My own father, of whom I was very proud, was a serious musician—an organist at the church and in charge of the choral groups, too. So he often worked nights, and more than ever around Christmas. When I was very little, I used to love to go with him, trying to take big strides like his and walk with my head held high, breathing in the sharp cold air. It was very impressive to sit in church and listen while he made the organ roar into a thunder of music. People called him “professor.” But the music was also an obstacle between us. My father wanted me to take music lessons, he tried terribly hard to teach me. And I was too charged up, I just couldn’t sit still that long!

Since my father had to practice a lot at nights and on Sundays, it was Uncle Charlie who took us to picnics and bazaars and on rides into the country Sunday afternoons. (I wasn’t keen on scenery, I thought it was a waste of time—you see how youth is wasted on the young?) Once he spent six-and-half-dollars trying to win a doll for me at a bazaar. She was a big beauty with dark, curly hair and I was crazy for her. He ended up buying the doll for me, and every Christmas my mother made her all new clothes.

My mother always sewed like an angel and she made all my clothes. The skirts were yards wide and the handwork so dainty, like the peach taffeta that I wore to be the poor little rich girl in the play. My dresses always had small round collars and big sashes tied into bows in back, something like my early costumes for pictures. All I needed was a permanent to be the happiest girl alive. I hated my straight, yellow’ hair that I wore bobbed to about the middle of my cheeks with the bangs straight across. I loved my bangs and never let them be cut until I couldn’t see through them. Uncle Charlie said I looked like an ad for Dutch Boy paints. He had a wonderful sense of humor and a laugh that rocked the joint, just like my mother’s. Later, when my pictures played Cincinnati, Uncle Charlie would go every day and laugh at anything even remotely funny. And I can still hear all of us laughing on that Christmas at his house—even if I was still on crutches and had no idea what to do next. I’d planned to be a dancer and now I couldn’t.

Oh how I’d love to go back East for Christmas! And I think we may do just that. When you read this, Marty and Terry and I may be zooming right into Cincinnati to join my mom. She lives in California, but she’s going home to the rest of the family for an old-time Christmas. To me, it will be better than an old-time Christmas, because Christmas means something different to me now, something holy and spiritual. We don’t give each other presents. What we do instead is to donate to charity in the names of all the people we love and want to remember. Only Terry gets presents, and he gets practical things, big bulky sweaters or something for his desk, or a radio—something he needs. I’d love to have him see the East at Christmas time.

The way it was in Boston, for example, my first Christmas with Les Brown’s band. We stayed at this small residential hotel where the guests had all lived for years and years and the rooms had crisscross curtains and fireplaces and big bay windows looking out onto the snow. It snowed up a storm and I remember sitting at the desk, looking out and writing letters home. Mother was with me. We’d go out into the snow Christmas shopping with Warren Brown, Les’ brother, who knew his way around town and guided us through the narrow, busy Christmasy streets filled with bustling people and bells and Christmas packages. Mother bought me three evening dresses, the first real formals I’d had. They were so pretty, and we sang carols as we walked through the streets.

After Terry was born, I’d either get home for Christmas or Mom and Terry would join me. Mother would come loaded down with all the baby equipment and jams and preserves and her own pots and pans, because she distrusted furnished apartments. They never had exactly what she needed to make exactly what she wanted, so she brought her own. The boys in the band would all go down with me to meet the train—they were happy to see her, I can tell you, because at one time or another, she’d feed them all. And home cooking tasted awfully good to fellows on the road.

One Christmas, though, we didn’t have together. I was in New York playing at the Penn Hotel and I’d be home ten days after Christmas. So it seemed wrong to have Mother and the baby come all the way to New York. We decided to wait and have our Christmas when I came home. I spent a month’s salary at the toy store, shipped their presents on ahead and settled down to be very brave.

Today I have tools to use against loneliness. I know you can be with people if you try. But I didn’t know that then, and I was lonely. I guess I’d have cried my way right straight through the holiday if not for the boys in the band. They were wonderful. We had Christmas Eve off and they arranged a party. I was living at the Penn but the boys were all doubled up in some small hotel. Four of them threw their two rooms together and when we arrived there was a tree set up, little presents from all the boys to me, loads of delicatessen food, and we all took turns putting through long-distance calls to home. Then, ten days later, I had another wonderful Christmas with the family in Cincinnati.

Another band Christmas was our first in California. I was in pictures, now, and had just bought the house in Toluca Lake. Mother and Terry came out that fall in time for Terry to start school. We felt like pioneers—we had a couch, chairs, beds, an icebox, and that was it! At Christmas we held open house and all the boys from Les Brown’s band were there—they came to cheer up Mother, because she was crying for Cincinnati. But Terry and I were on Cloud Nine. I was in pictures, and he was cowboy-minded. All you needed was to have Santa arrive with a load of six-shooters and spurs, and Terry was in small boy’s heaven.

Our Christmases began to be truly wonderful when Marty came into our lives. I certainly remember that first Christmas Terry wanted to buy Marty a present and he got Mom to take him to the dime store, carrying with him a huge piggy bank full of pennies, nickels and dimes. Can you imagine the Christmas rush in the dime store? The crowds and the hurry, and Terry dumping this bank on the Hoot, every penny? And what do you suppose he bought Marty after all this? Garters! He bought him a pair of garters and me a scarf to wear around my head—such stiff material it wouldn’t bend, much less tie!

Marty’s family had never made a big fuss over the holiday but he took to it like mad. To this day, two weeks ahead of time he’s out looking for a tree, which is usually drooping by the time Christmas is here. He almost breaks his neck climbing up to take care of the lights, the wreath and all the house decorations. And, of course, it’s Marty who has helped me arrive at the true meaning of Christmas, the deep, spiritual meaning of it.

You learn as you go along; your values change. When I was a kid, growing up meant a bra, a permanent, high heels and false teeth. Those four things I wanted madly. My grandmother had uppers and lowers and I loved the clack they made But you learn as you go that growing up is none of those things, it’s a matter of living and seeing the good—absorbing and accepting the wonderful gift of life. I realize that my Christmas memories had very little to do, actually, with gifts. They’re all about the people who made Christmas beautiful by giving me the gift of love.

That’s why I’d love to go back East. I’d love to pop into Cincinnati and see all the family, Aunt Marie (Marty calls her “The Rock”) and my friends. You know, there are twenty-five of my old girl friends living there? When we get together it’s a real bash. They call me “Doke,” and we tell all the old stories, but we have such fun.

I’d like to pick up a rented car, go on to New York, spend a week exploring wonderful New England antique shops, go up through Maine, and visit Marty’s home in New Adams, Massachusetts. The brisk weather up there—oh, I can just smell it! We’ll pick up jams and jellies and cold crackling baskets of apples to send home. . . .

At Christmas, it’s such fun to remember all the people who’ve meant a lot to you, write to them, tell them you’re thinking of them . . . but more fun, still, to pop in and tell them in person . . . and that’s really what I want to say to all of you who have become part of my world. With all my heart I say it:

“May you have a joyous and a holy Christmas.”

THE END

Be sure to see Doris Day in U-I’s “Midnight Lace” Hear her sing for Columbia.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1961

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments