A Father’s Prayers For His Sons—Audie Murphy

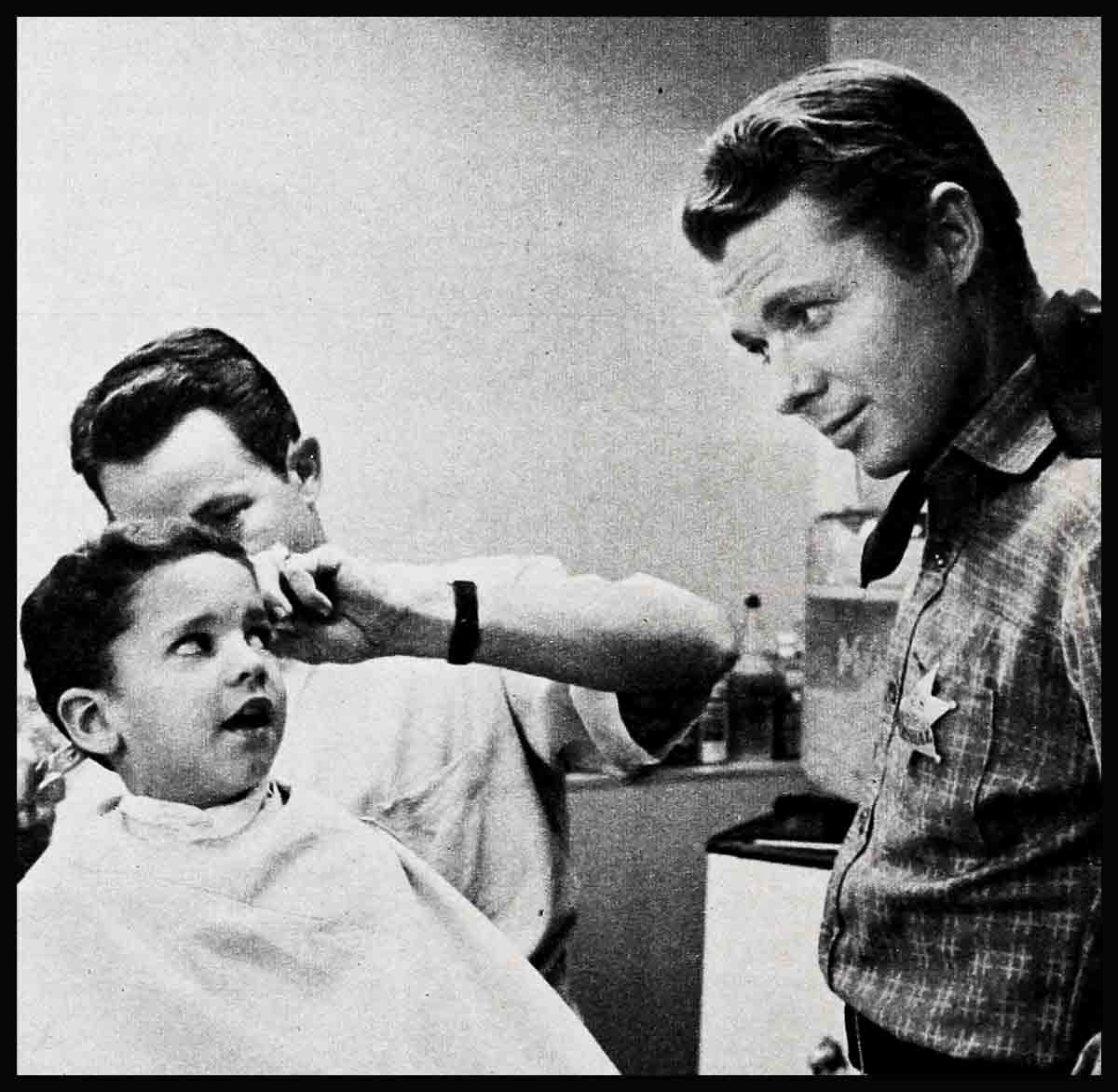

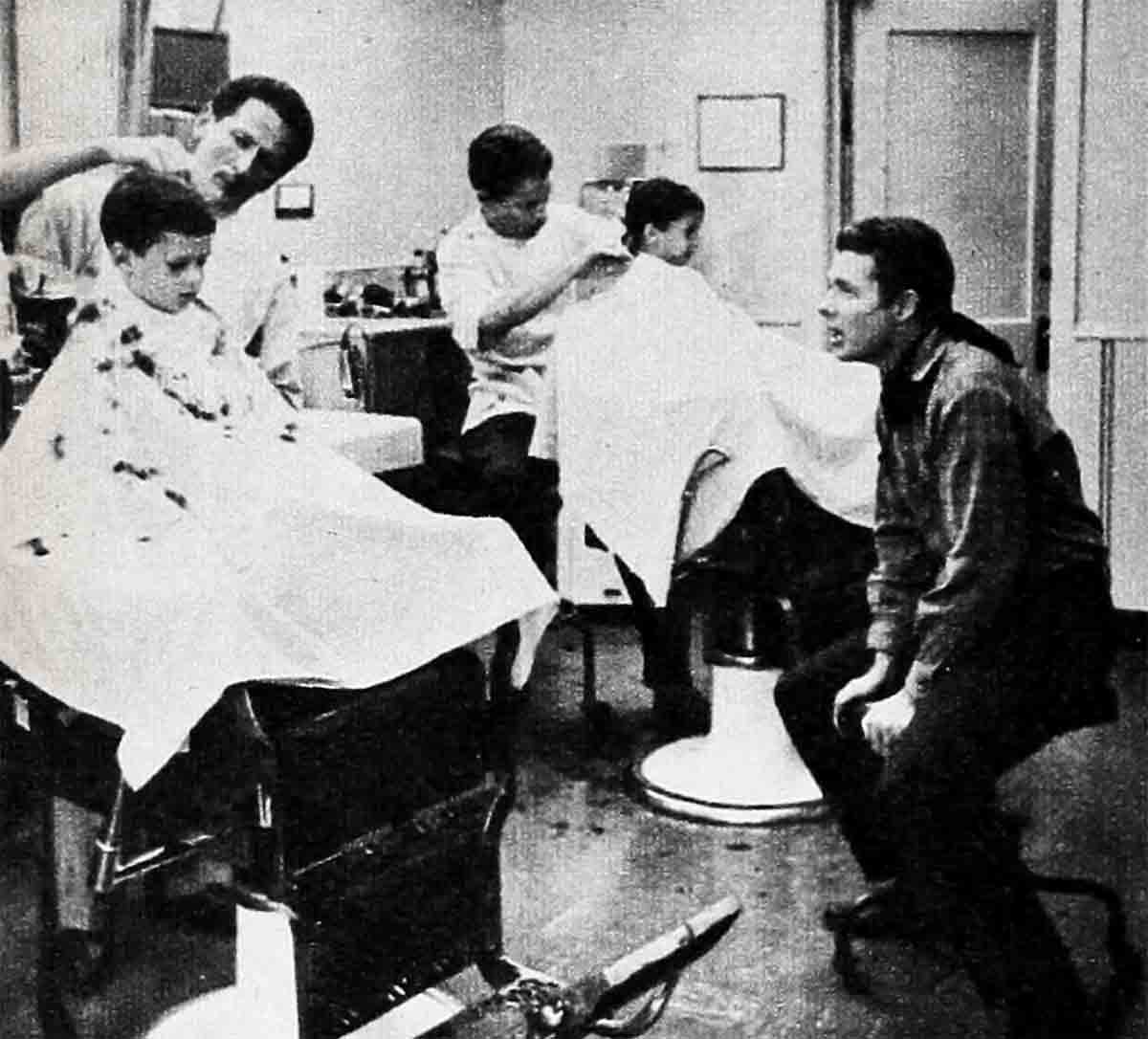

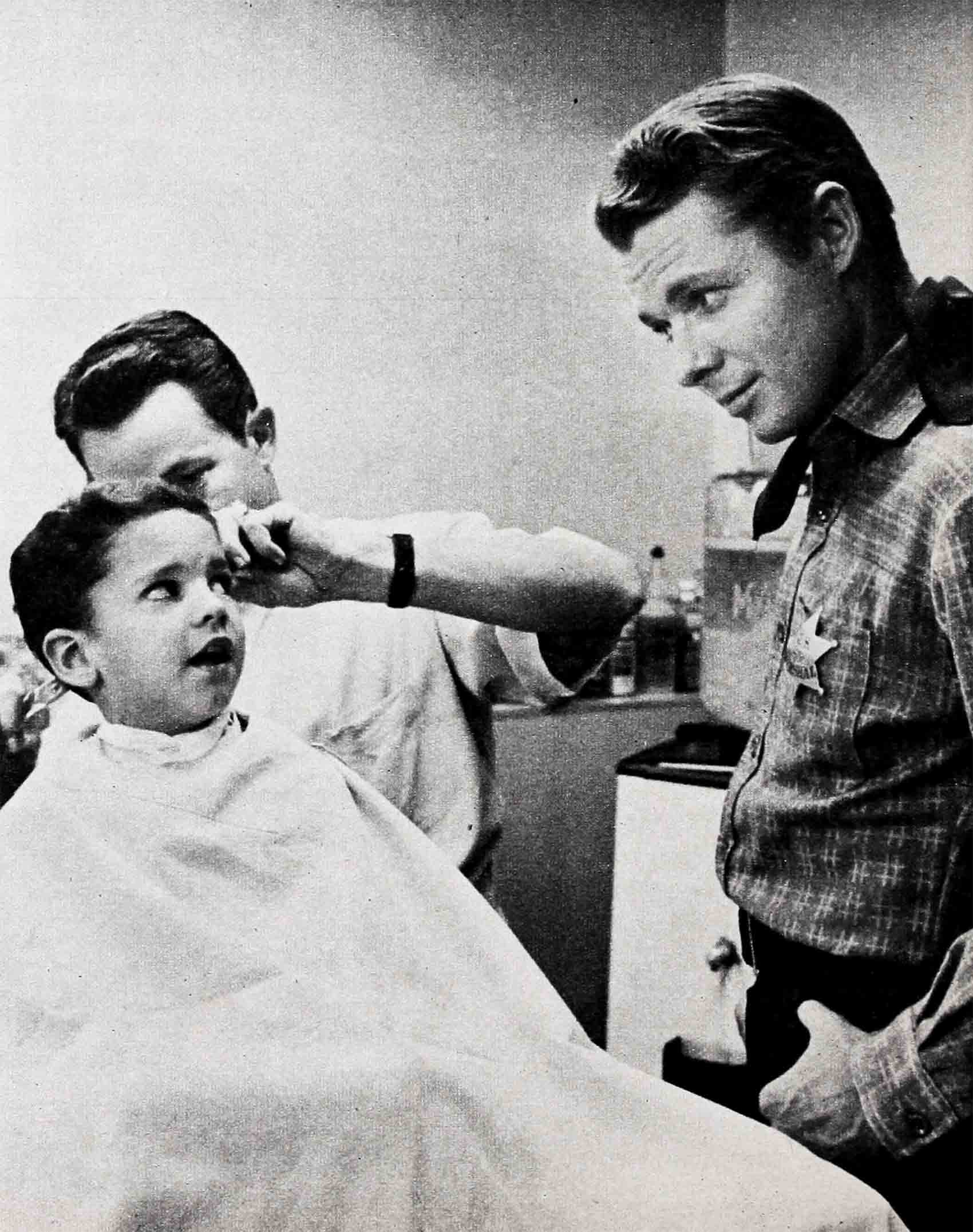

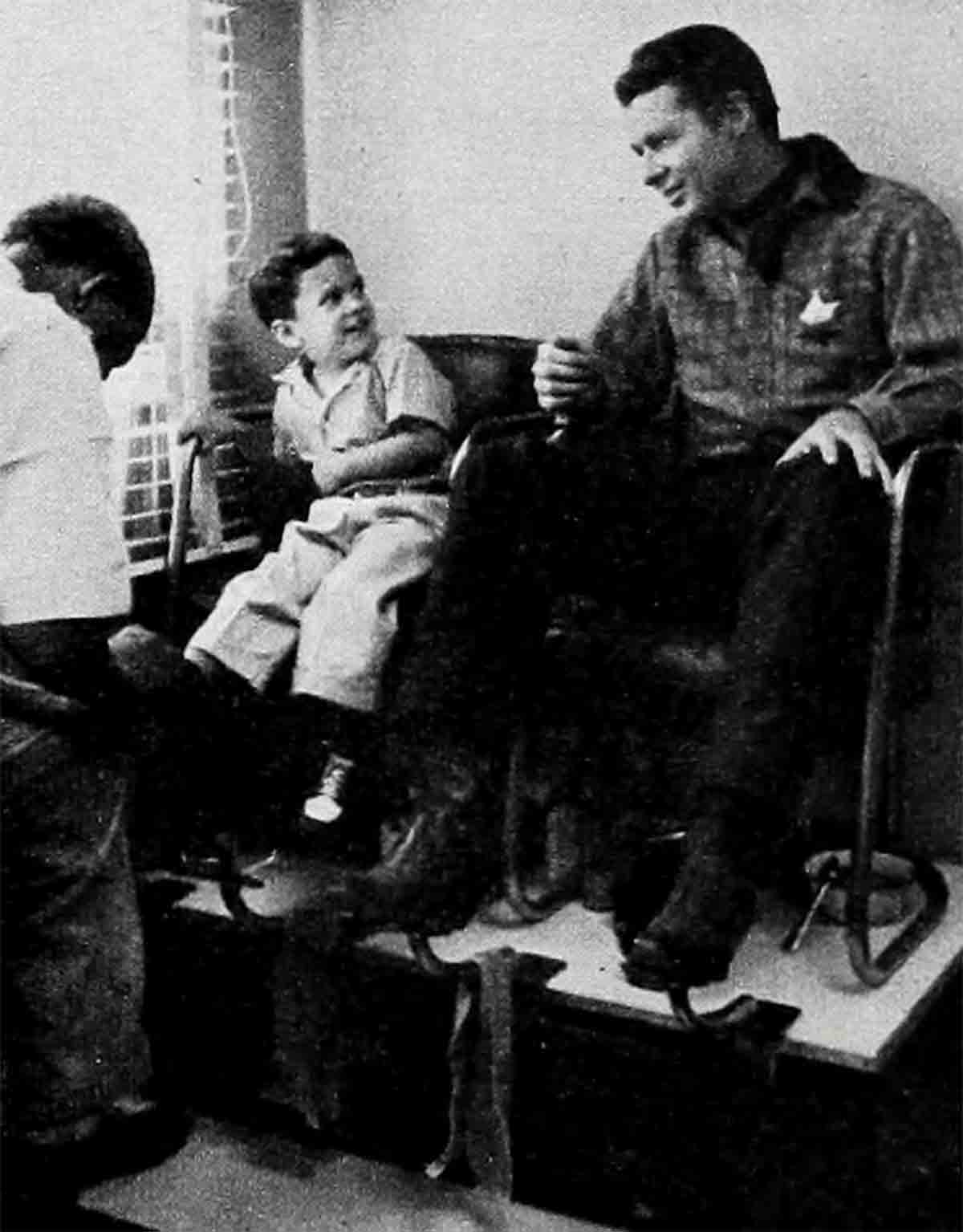

In the big leather chairs of the barber shop at Universal-International Studios, two little boys sit, quiet and still and good as gold. They are Jimmy Murphy, age three, and Terry Murphy, age five, and they are no angels. The reason for their model behavior is the glorious reward it always brings—a real grown-up lunch with Daddy in the studio commissary and a visit to the Injuns. Fire Injuns, that is. And they make up for all the trouble.

The morning sun casts slanting shafts of light on the polished linoleum. The only sound is the snip, snip, snip of the barbers’ shears. Leaning against the wall, Audie Murphy closes his eyes . . . and in his heart, there is a silent prayer . . .

Dear God, thank You for giving me these two wonderful, healthy sons. Thank You for giving me this day, and all the other days, to share with them the finest, purest joy in life, the joy of childhood. It’s something I never had before, but now I know that You didn’t deny it to me, because I have it, through them, and this way it’s doubly precious. Help me to keep it for them, as long as I can. Help me to keep some of it alive in our hearts, always . . .

The sound of the scissors stops, and Audie, whose hearing, trained in the terrors of battle, will always be supersensitive to the slightest change of sound, is startled.

The haircuts are finished. Terry’s barber picks up a white bottle and cocks his head questioningly. “Wet it a little, Audie?” he asks.

“Guess a little won’t hurt,” Audie answers.

The barber administers the finishing touches, and whisks the pencil-striped cloth from the boy’s shoulders. Terry clambers down from his lofty perch. Eagerly he reaches for the candy bar his dad offers. He flashes a big smile, disclosing a gap in the bottom row of tiny teeth.

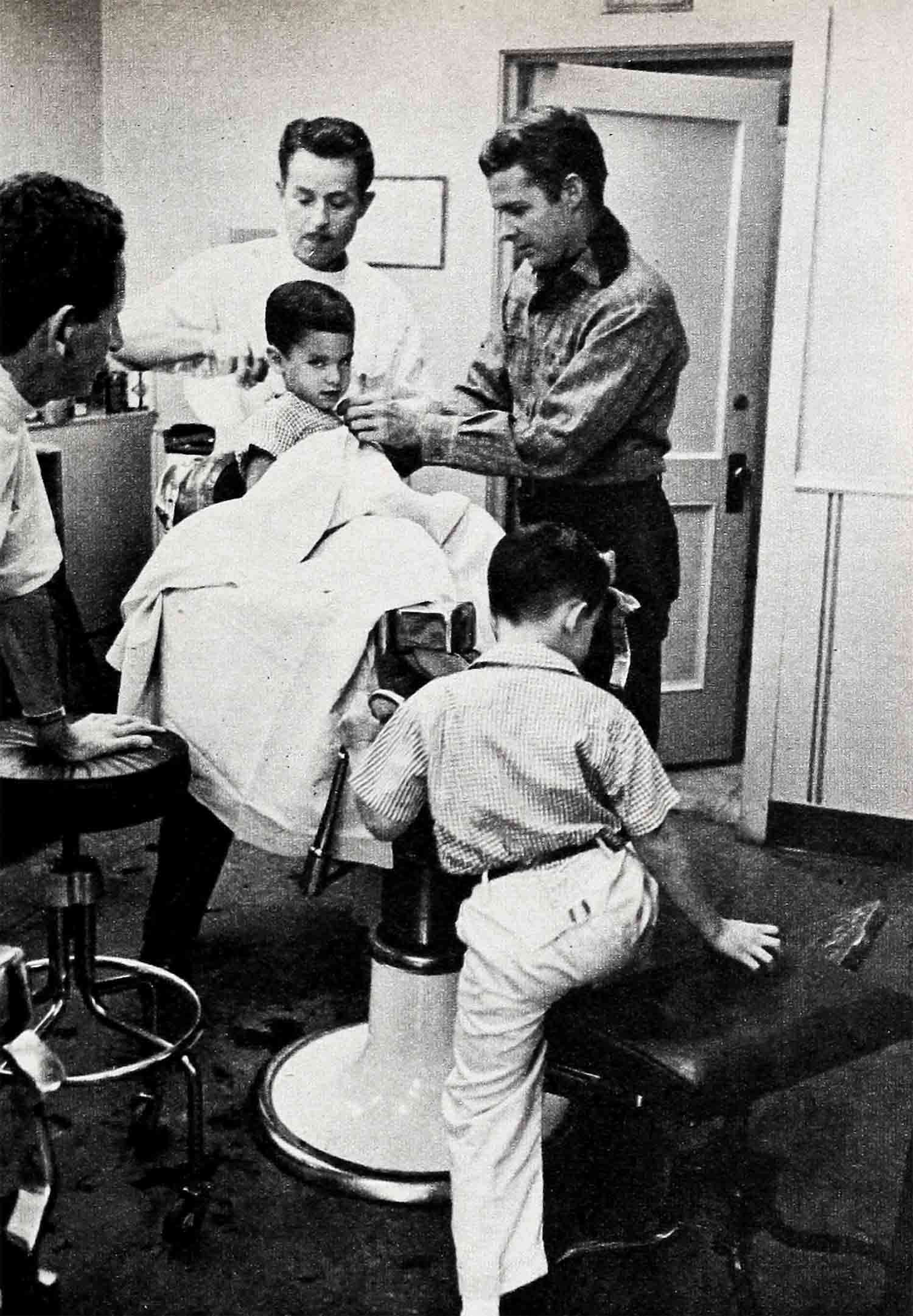

Terry fills the abyss with a generous mouthful of candy. Thus fortified, he prepares to scale the next mountain—the shoeshine stand. The bootblack helps him up.

Now brother Jimmy wriggles off his barberchair. He stands questioningly before his father. “Me, too?” Audie digs deep into the pockets of the sheriff’s outfit he’s wearing for “Middle of the Street” and fills the small outstretched hand. Jimmy fumbles with the wrapper. His anticipation gives him ten thumbs. He hands it back to his father. Audie peels the paper off, breaks it in two quickly and palms one of the rich brown chocolaty halves.

“The whole bar would be too much for a little guy,” Audie murmurs. “Spoil his appetite.”

Bootblack Chuck beats a final tattoo on Terry’s yellow cowboy boots.

“Just a lick and a promise, Chuck,” Audie advises. “Got a lot of stops to make today.” Chuck works quickly while Audie pays the $3.00 for the haircuts.

“Okay, wrecking crew—let’s get those jackets on!” Audie calls. As the boys turn to him, he notices the damage the candy has inflicted. “Oh-oh, hold up there,” he says. He turns to the barber. “Got a cloth I can use?” The barber dampens a towel, hands it to him. Audie bends and with a touch surprisingly gentle for a man wipes the chocolate smears off both pairs of hands and faces. From the job he does, it is obvious he is no once-a-month father. He even detects and dabs off the wisps of hair in and behind the ears. The boys are good, well-be-haved. They squirm only a little. Audie helps them into twin Ike jackets. He holds the door open for them, and says the goodbyes.

When he turns to follow his charges, they’ve already run to the candy stand outside the barber shop. Two small noses are pressed so hard against the glass that it would take a bulldozer to pry them loose. Audie smiles, and lets them take their time.

To Audie Murphy, at Terry’s age, a candy store was an unheard-of wonder. He was already working in the fields, on the sixty-acre farm near Kingston, Texas, where his father was a sharecropper, trying to help him and his ailing mother eke out a bare living for themselves and nine children. He had only one toy. A slingshot. He was taught to hit rabbits with it. They needed the rabbits for food. When Audie was fourteen, his father walked out. Two years later, his mother died. Audie tried hard to make a home for himself and three younger children—the older children had married—but it was impossible. The three youngsters were taken to an orphanage. And Audie, fibbing about his age, went into the Army. Now, thinking of those days, his heart is full . . .

Dear God, I am so grateful that You have given me the means to keep my sons free from want—and what is worse, the fear that comes from poverty and hunger. But please, help me to make them understand that they should never take the good things in life for granted. And help me to make them see that it is not having, but giving that gives happiness . . .

“Daddy!” Terry calls, ready to begin negotiations. “Could I have some Chick-a-lets?”

“Could I get one of those, Daddy?” Jimmy cries. He gets a turn-down. It’s not because Terry is favorite son. It’s just that Jimmy has pointed to a box of Havana cigars. He is persuaded that he will enjoy “Chick-a-lets” more.

Now Terry has drifted to the comic books. “What kind is this, Daddy?” he asks.

“That’s Robin Hood.”

“Could I have it? I like Robin Hood!”

Audie nods his head patiently. “Okay, let’s get the show on the road.”

He realizes, with a start, that these are the same words he used so many times when he was a platoon leader in Europe.

He doesn’t want to think about that now. Long before he dreamed of having sons of his own, he gave away all his youngsters—he was always crazy about kids. His Congressional Medal of Honor went to a small Does he regret it, now that he They’ll find out soon enough.

And then? As sons of a Medal of Honor winner, his boys are automatically eligible for West Point. He’d be pleased and proud if they choose it. It would be a fulfillment of his own dream—he’d applied to go to West Point, but his war injury ruled him out. But, at the thought of what a soldier’s life can mean, a cold perspiration breaks out upon his forehead. Audie Murphy knows what war is, as only a man who can entered the blazing inferno, who has killed and had his best friend’s bullet-riddled body fall upon him, can know it.

Dear Lord, keep my sons, and all people everywhere free from the horror of war. Give us wisdom, to find a better way to solve the world’s problems. Help me to guide my sons, to develop and educate them so that they may do their part to make this world a better place. But help me, too, to show them that the freedom in which we in America live is a very precious thing. A thing worth fighting for, if need be . . .

“Daddy,” asks Terry, “can we see the injuns?”

To Terry, he is—in the best Spock tradition—friendly but firm. “A little later,” he says. “First we’re going to the Photo Gallery to take some pictures. You know—where they’ve got that hobby horse.”

It sounds like fun to Terry. “Let’s go, Daddy,” he says.

The Gallery idea is not spur-of-the moment. Audie wants some fresh pictures of his sons in his wallet to replace those well-worn on the Saigon location for “The Quiet American.” And the boys have grown so much. Ray Jones, winner of a half-dozen Academy Awards in the now extinct “still photograph” category, has offered to help his buddy Audie out.

“Three Murphys here to see Ray,” Audie announces as he shepherds his flock into the Jones studio. The photographer pops out of his inner office, smiling broadly. “We’re ready for ’em,” he says. “Got the hobby horse saddled up and ready to ride. “Who’s on first?”

“Well,” says Audie, “let’s double ’em up.” He helps the boys mount the dappled steed. Ray locks and loads the big tripod camera. He signals his readiness.

“Giddyap,” says Audie, hoping for a pair of quick grins.

Jimmy leans forward, slaps the horse’s rump, and laughs happily. Terry’s face shows signs of ennui. Apparently, he has decided that a rough, tough cowboy who’s ridden his dad’s quarter-horses—real live ones—shouldn’t get too excited over a little old wooden horse.

While Ray keeps the shutter clicking, Audie tries different approaches.

“Who’s first in the bathtub tonight?” (“I am” shouts little Jimmy. Terry has no comment.)

“What’ve I got here, fellas?” (“A squeaky mouse,” cries Jimmy. Terry remains noncommittal.)

“What you gonna do when we go visit in Texas?” (That one strikes oil. “Ride horseback upside-down,” says Terry with charming little boy illogic. He grins a cantaloupe-slice.)

Ray clicks the shutter. The session continues a few minutes longer for “protection.” And for some individual shots. But they have what they came for. They have captured on film that elusive, precious commodity—a child’s smile.

Leaving the Gallery, they pile into Audie’s new Olds sedan. They roll out the Universal-International Studio gates, and head for Nudie’s Western Clothing shop in Burbank—where Audie is to have a fitting of additional outfits for the new film.

Inside, Audie heads for the fitting room. Nudie—short, barrel-chested and bespectacled—cautions his assistant. “Those fancy duds—the rodeo clothes—Audie won’t wear ’em. He likes the simple well-tailored things.”

“Doesn’t surprise me,” the man replies. “Look at him. He could wear cashmere—he’s wearing wool. I’m sure he could afford a Cadillac—he drives an Olds.”

“That’s right,” says Nudie. “And he could live in a swanky suburb like Beverly Hills. Instead he picked a nice comfortable neighborhood right here in Burbank. Wonderful guy—that’s why!”

Audie saunters up. Nudie changes the subject. Audie would rather break an arm than hear someone deliver bouquets about him.

“Anyone care to hear the new threat to Elvis Presley do a performance?” he asks. “Terry wants a new hat to take the place of the one a dog chewed up, so I made a deal with him. He sings ‘Hound Dog’ and he gets the hat.”

He holds aside the curtain to the little fitting room. Terry stands there, guitar cradled in his arms. It seems set, but he doesn’t.

“Ready?” Audie asks.

Terry’s eyes study a clothing tag lying on the floor. He doesn’t answer, at first.

“Well, Daddy,” he finally murmurs. He beckons his father to him shyly. The father kneels so his son can reach his ear with a whisper. He nods at the words.

“That’s fair enough,” he says. He raises and drops the door flaps. “He’d rather not have a studio audience,” he explains. No sounds come from within. Then Terry’s courage returns. We hear music—on key, too. “You ain’t nuthin’ but a hound dog. You ain’t nuthin’ but a hound dog.”

Audie lifts the flap a trifle so they can sneak a peak. Terry—hips rolling wildly—is doing the whole Elvis. Then he stops in mid-phrase as his eyes lock on us. He raises the guitar on high as if to dash it to the ground. He holds it there. Everybody laughs. Terry lays his guitar down.

“Good singing, boy!” says Audie. “Come on out and pick out the new hat.”

In the car on the way back to the commissary, the boys have a great time trying on the hat. And Audie feels a sudden warmth and tenderness sweep over him. Again, he prays . . .

Dear God, I don’t care if my sons aren’t geniuses, and don’t make millions. All I want for them is what I’ve found myself—a family. Having them, having someone to belong to, has changed my whole life, and I thank You for it. I’d like them to have that happiness one day. Only that, and nothing more. Because, I think, it’s everything.

Help them, too, never to lose the joy in little things. Like that hat. It isn’t much, but to them it’s so great. If they can only keep that, it will mean so much to them . . .

The Sun Room of the U-I Commissary is the dining room of the stars. Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Rock Hudson, Jeff Chandler, John Saxon, George Nader—they all lunch here. And all are given royal service. But Terry and Jimmy Murphy rate even higher. They are allowed to scoot directly into the kitchens Seconds later, they are back—biting great toothy arcs into slices of thickly buttered rye bread.

Waitress-dietician Mabel Hurt dispenses the menus. She dispenses a special smile for Audie. He has lunched here on and off for almost ten years.

She sets up a youth chair for Jimmy and offers another to Terry. He spurns it politely but with finality. “That,” his look says, “is for babies. I am a man!”

Audie orders tomato juice and curried lamb with a hot sauce. Terry orders a ham sandwich and a soft drink. Jimmy seconds the motion. Whatever big brother wants, he wants, too.

Terry remembers something.

“We gonna see those injuns soon?” he inquires.

“Right after lunch,” says Audie.

“We better go soon or I’ll bust somebody right in the mouth,” says Terry matter-of-factly.

“You’re gonna get me cotton-pickin’ mad with that kind of talk,” Audie says. Terry is repentant.

“That was just TV talk,” Audie explains to Mabel. “Kids hear adults talk that way on shows. They don’t know it’s wrong ’till you tell ’em.

“They say,” Audie adds, “that if you leave kids to their own devices, they’ll choose the foods that are best for them. Somehow I don’t quite believe it. I’m half afraid mine would live on soft drinks and Toll House cookies.”

The boys take a couple of bites, nibble aimlessly at a pickle. They seem to be waiting for something. They are—the dessert course. When the cookies arrive, their missing appetites suddenly do, too.

Terry is ready with the big question again. “Now can we go see the injuns?”

“Now,” says Audie. They drive to the fire department. The doors are closed though, and no one is in sight.

“Must have been up late at a fire, Audie says. “I guess they’re still sleeping. We’ll just have to make it another time.”

Terry pushes the point briefly, but Audie is firm. The firemen must get their sleep. Terry, realizing that he has met an immovable object, has another idea.

“Well,” he says, “we could chase a bus instead, and you could drive up real close, and I could climb out the window and jump up on top, and hang on, and then open the window, and climb inside, and then I could sit down behind the driver, and when he turns around—well, he’ll be very surprised.”

Audie, knowing that this is just small boy talk, smiles at the imaginative speech, but makes no effort to locate a bus to chase. This is all right with Terry. From the distant look in his eyes, it is apparent that in his mind’s eye he has already overhauled the bus and is sitting behind the driver at this very moment. In fact, he is already planning his next caper.

They make the trip from the studio to Burbank in a few minutes and wheel into a lovely tree-lined dead-end street. There are many nice homes on the block, but the nicest is the one at the dead-end. It’s Early American with rich-looking dark wood planking on its exterior, and it straddles the end of the road. Audie seems to have selected the house as wisely as a general selects a position. It stands on the edge of a golf-course with a million dollars’ worth of landscaping around it.

Once inside, Jimmy and Terry disappear upstairs, to show off their haircuts and their shoe-shines to Mother. Waiting for them downstairs, Audie Murphy stands looking at his gun collection. He looks at it a long time.

He never uses the guns anymore. He cut down on hunting trips first, because they took him away from the family too long.

Then, one night, they’d been watching TV. A flock of geese came on the screen, and the hunters started firing at them. Then there was a closeup of the hunters proudly holding the dead birds. Terry jumped up, ran for his cap pistol, and passionately fired at the screen. “Bad men!” he sobbed. “Bad men!”

Before the locked gun case, Murphy humbly bows his head.

Dear Lord, I have been asking You to help me guide my sons. But I didn’t think of the most important thing. I want to thank You for what they have taught me. The Bible says, “A little child shall lead them.” Help me, help all of us, never to forget that. Amen.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1958

zoritoler imol

24 Nisan 2023I am impressed with this web site, very I am a big fan .

Flanders

20 Ocak 2024You are so interesting! I don’t believe I’ve read a single thing like this before. So wonderful to find someone with some unique thoughts on this subject. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is needed on the internet, someone with a little originality.